The word mi’zar can signify a pair of trunks. This meaning is specified by Lane, who says that mīzar and mi’zar are currently used in Egypt to designate "a pair of drawers."

In Maliki law, it is stated that "No man shall enter the bathhouse without a mi’zar" (thus in the Epistle of Ibn Abi Zayd). In al-Nuwayri's Ultimate Ambition we find that al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah forbade anyone to enter the bathhouse without one, and this is reported by al-Maqrizi as well. And in Ibn Iyas, we read in a report of the year 824 AH/1421 CE that "When they went to wash the corpse of al-Malik al-Mu’ayyad, they could not find [in the sultan's domicile] the smallest ewer to douse his body with, and no towel to dry his beard until one of the washers of his corpse gave up his own handkerchief. And there was no mi’zar to shield his privates until they took one off a neighborhood mourner—a coarse black wrap of Upper Egyptian make. Praise to the One who glorifies and brings low!"

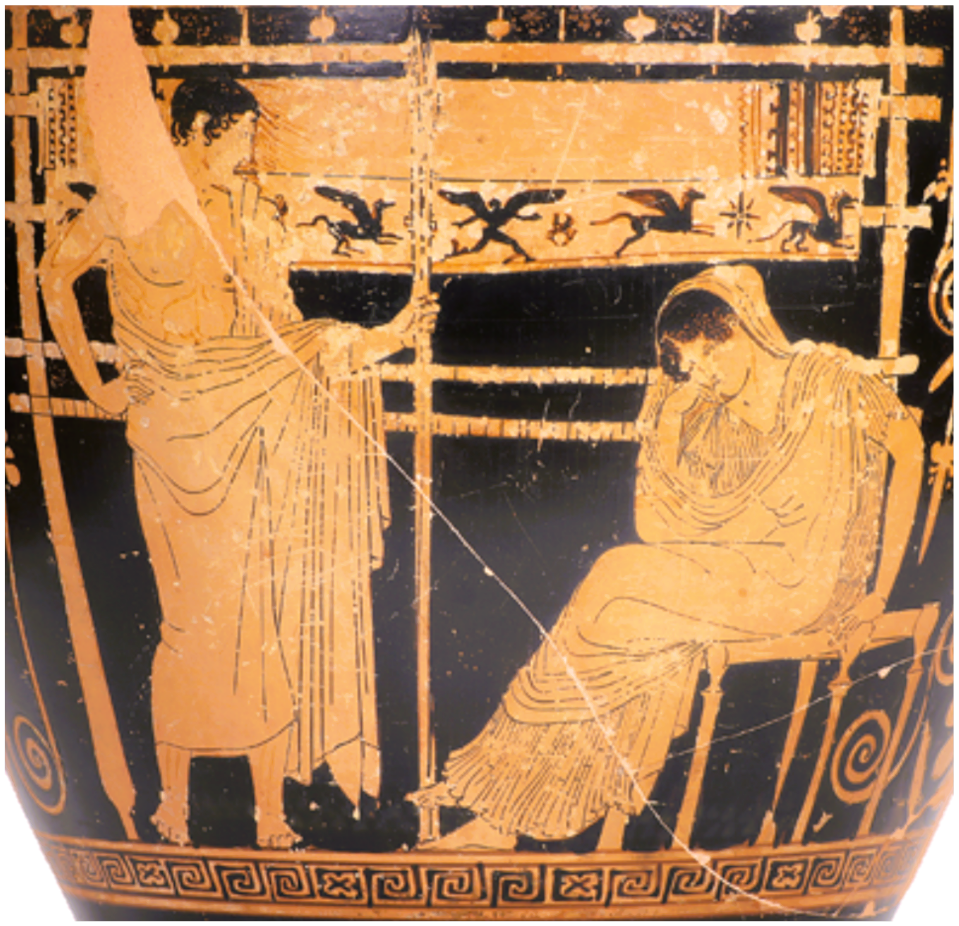

Freytag defines mi’zara only as [the brief cloak called in Latin] a pallium, but it also designates a cloth that covers one's private parts and lower body. In his Travels, Ibn Battuta tells of "a beautiful shrine at Burj Bureh [modern Brijpur?] inhabited by a handsome, clean-living holy man called Muhammad the Naked, because he goes dressed in nothing but a waistcloth covering his navel, with the rest of his body exposed. This man is a pupil of the righteous saint Muhammad the Naked who dwelt in the Qurafa cemetery of Cairo—one of God's saints who went robed in nothing but a mi’zara [appearing as tannūra "kilt" in most manuscripts of the Travels], which is a waistwrap that hangs down from the midriff."

Mi’zar can signify a cloak as well. In Ibn Iyas, we read in a report of the year 822/1419 that "the Sultan [al-Mu’ayyad] wore a white woolen tunic. On his head was a small turban with trailing fringes, and he draped a mi’zar of white wool over his shoulders in the Sufi fashion." And in [the tale of Muhammad ibn ‘Ali the Jeweler, a.k.a. "The Strange Caliph" from] A Thousand and One Nights: "He threw a black mi’zar over them, and from beneath it they began to watch."

Among the garments of the monks of St. Anthony "on the slopes of Mt. Colzim," Vanslep describes the mezerre: "a great cloak of black material lined with white, sometimes called melótēs in Coptic, and sometimes bírros. It is like the cloaks of the Jesuits, only it has no collar, and except when traveling, they seldom wear it." [As mentioned above,] mi’zara is defined as pallium in Freytag's Lexicon, and Vansleb may had this form in mind when writing mezerre; similar though these words are, mi’zar is not at this time used to name that garment in Egypt.

Lastly, the mi’zar can be a covering for the head. In his Travels, Ibn Battuta describes a particular form of mourning observed at Idhaj after the crown prince's death: "I happened that day upon a strange scene. The place was packed on every side with judges, orators, and nobles seated with bowed heads along the walls of the royal gallery, some of them weeping and others merely pretending to. Over their clothes, they wore rough, sacklike robes of raw cotton turned inside out, and every man's head was covered with rag or a black mi’zar. To those who kept this up for forty days, the sultan gifted a new set of clothes."

It is in this sense that mi’zar entered Spanish as almaizar, defined by Covarrubias [the same] in his Treaury of the Castillian or Spanish Language as "a mantle-like veil or toque worn by Moorish women. It is made of fine silk, with colorful borders and fringes at either end." He continues: "Diego de Urrea says this garment is called in Arabic an izār, explaining al- as the definite article, and ma- as the marker of the instrumental noun: al + ma + izar = almaizar 'covering,' which the Moors wrap around their heads, leaving the fringes to hang down over their shoulders." Throughout early Spanish literature, almaizar and almaizal refer equally to head coverings for women and men.

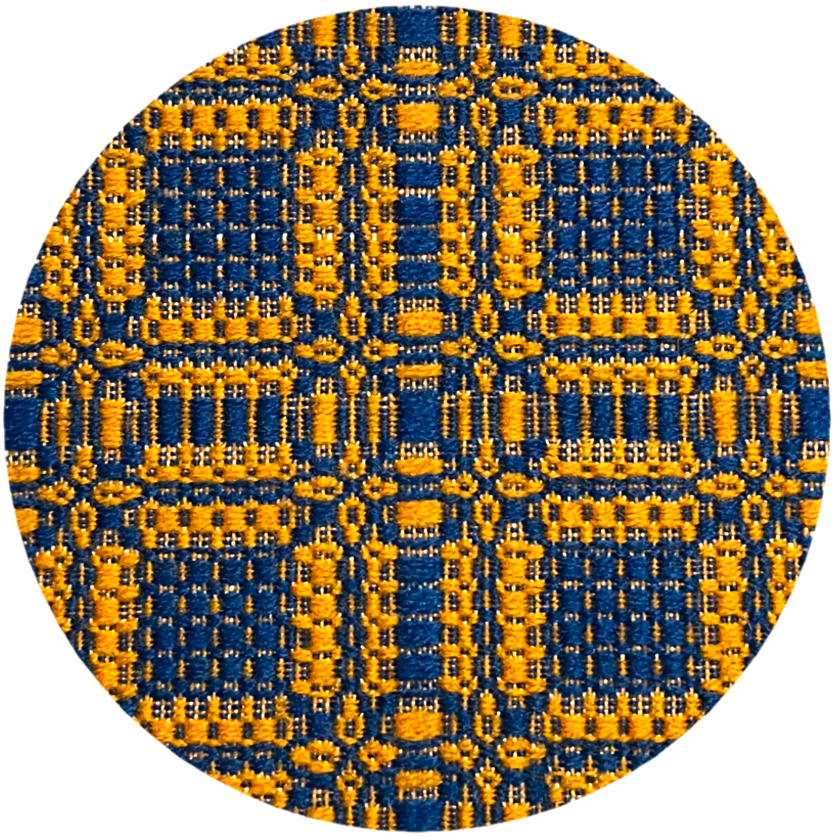

Mi’zar has also entered Italian: large panels of printed cloth with which women wrap their heads are called in Genoa mezzari. As for mi’zār (with long alif), that's one form I don't believe I've ever come across in Arabic.

From A Detailed Dictionary of Terms for Arab Dress (Amsterdam, 1845)

by Reinhart Dozy