Unraveling the Riddle

of the Thread

It's smart to move on from a subject after publishing about it. Continued study can lead to mournful discoveries of things you wish you'd said, or hadn't. That hasn't quite happened with "The Riddle of the Thread," my article that came out two years ago, but I did just have a close call, and for my own reference (if no one else's) I need to create this record of it.

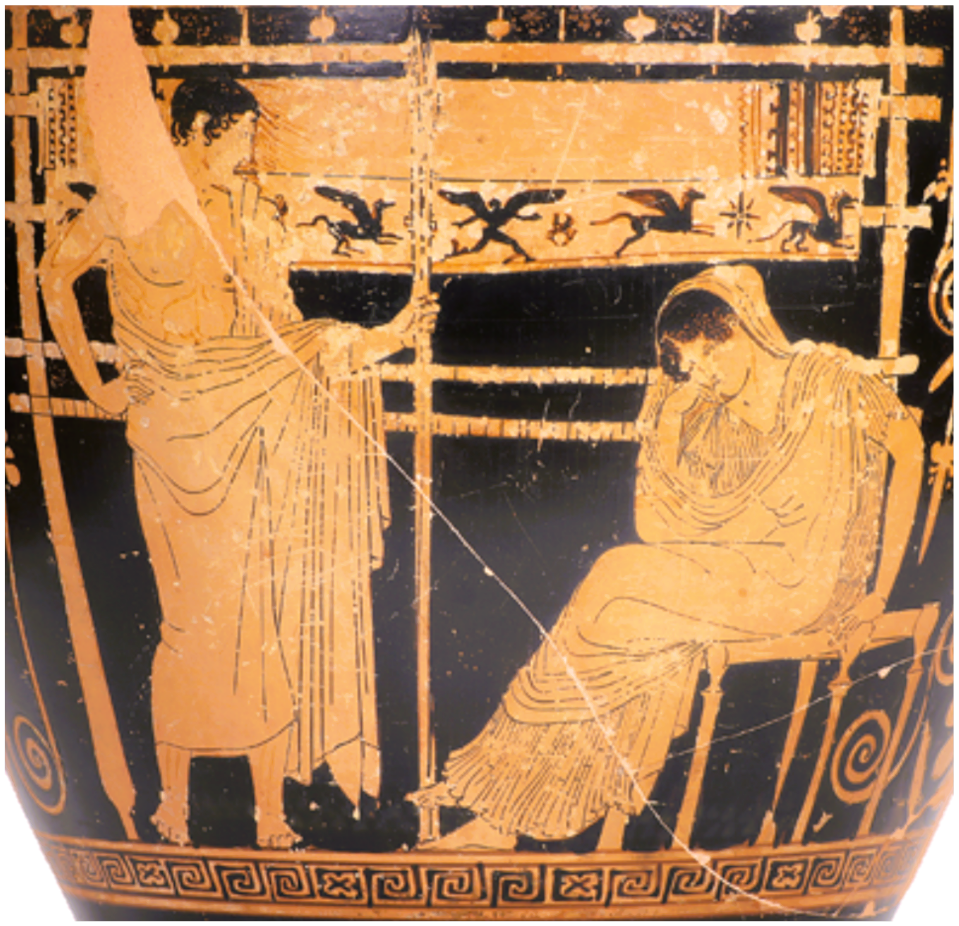

The idea for the article was to treat the subject of spinning apart from Hands at Work, so as not to weigh the book down or risk confusion in readers' minds with weaving, which is the book's main focus. (Even Gandhi got the two crafts mixed up, early in his career.) "On the subject of spinning, please see Larsen (2023)" is all I planned to say, until my recent encounter with a text of al-Ṣafadī's previously unknown to me: Faḍḍ al-khitām ‘an al-tawriya wa-'l-istikhdām (Breaking the Seals on Ambiguity and Polysemic Usage). If only I'd had this book five years ago! My 2021 article on abyāt al-ma‘ānī would have been much improved by al-Ṣafadī's classification of ambiguity in its various types (and a comparative reference to Empson's wouldn't have hurt either), though no one who reads that article will complain that it's too short.

With regard to "Riddle of the Thread," my chagrin is double. In the first place, al-Ṣafadī upholds my thesis admirably, and I wish the article reflected this. In the second place, he discusses an idiom, apparently well known, that almost overthrows something I say on p. 67. Remarking on the near-homophony between the ghazl of "spinning" and the ghazal of "amorous discourse" which lent its name to the genre of poetry, I not only said that it went unplayed-on by Arab poets, but that "If any evidence could be found to align poetic composition with spinning in the early poetic record, it would certainly undercut the argument put forth here." Thank goodness for the word early! because the idiom in question emerged in the Mamluk period, but it did become commonplace, and some awareness of this would have strengthened "The Riddle of the Thread."

The idiom is hard to translate. It derives from an old metaphor, where the look in someone's eye is said to "speak aloud" though no words are pronounced: "Eyes have logos when mouths are silent," goes one verse by ‘Abd Allah ibn Mu‘awiya (d. ca. 130 A.H. / 747 CE), and this is so conventional it could be by anyone. Was I not just reading in Colette about someones' "eloquent eyes"?

Any verb of speech may be used in poetry for the logos/manṭiq of the eye. It was therefore inevitable that ghazila yaghzalu "to engage in amatory discourse" would serve this function, because it is esssentially a verb of speech. And so ghazal came to stand for "seductive looks," which kind of makes sense, but what happened after that suprised me. Poets did come to play on this verb's near-homophony with ghazala yaghzilu "to spin," and I should have seen it coming. Just because Ibn Faris opined that ghazal and ghazl are alien to each other doesn't mean poets can't splice them together. So the vocabulary of spinning came to be used with reference to seductive looks—not because the act of spinning is seductive, but because ghazl and its cognates substitute playfully for ghazal. When al-Ṣafadī talks about the paronomastic transfer of attributes from one entity to another, resulting in "ambiguity that is far-fetched" (al-tawriya al-ba‘īda), this is what he means.

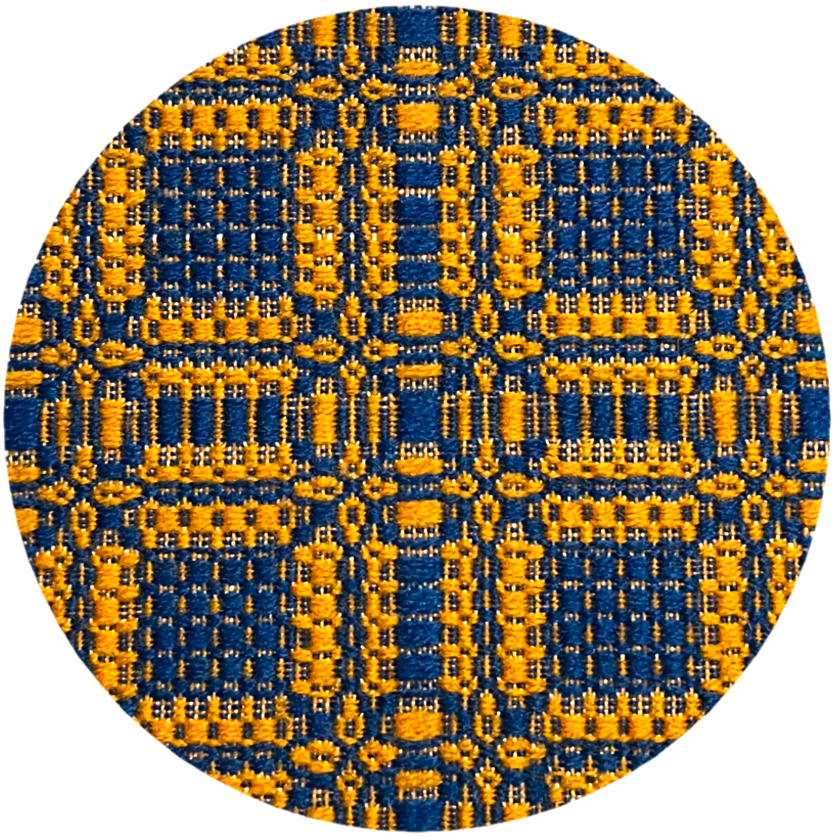

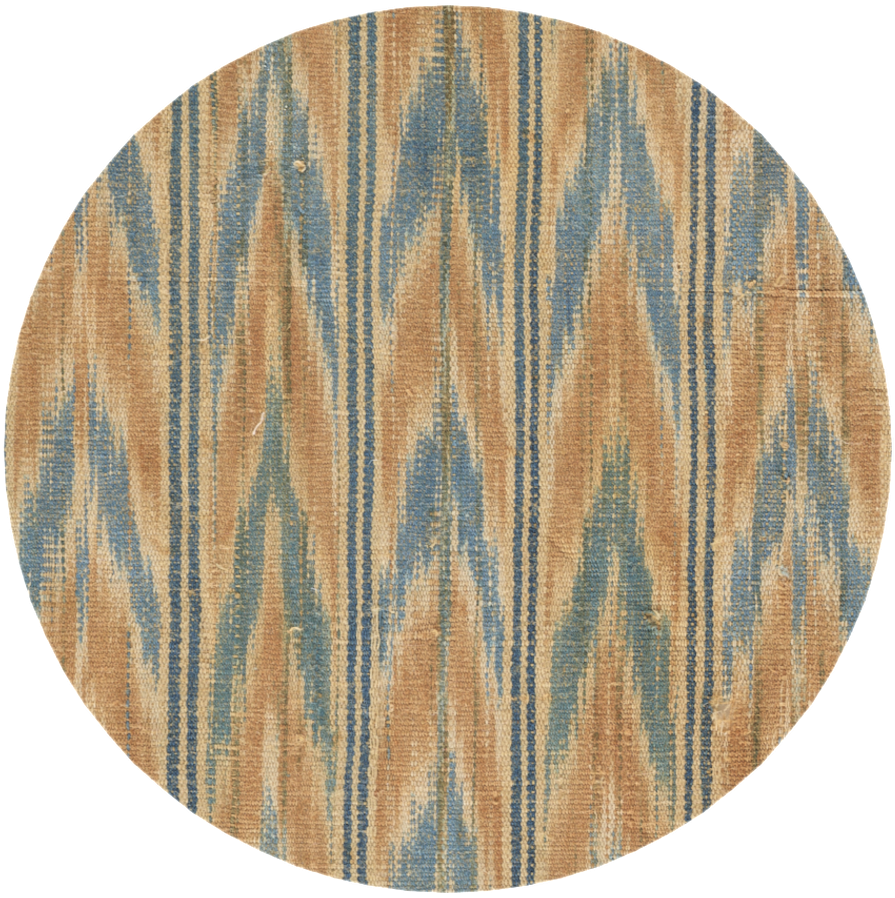

Nor did things stop there. The idiom was enlarged (somewhat absurdly, if you ask me) to include the figure of a widow at her spinning, as a proxy for the beloved's bewitching eye. (Last night's post from Faḍḍ al-khitām ends with two examples of this). For an example that combines spinning with weaving, we can thank al-Ṣafadī's contemporary Shihāb al-Dīn al-Ḥājibī, as quoted by al-Badrī (meter: wāfir):

In her kohl-rimmed eye are ghazal and ghazl.

In my eye, only tears.

The darting gaze of her eye entrances.

Yours is the eye that spins and weaves

If the ghazal of amorous discourse can be enmeshed in the ghazl of spinning, how about the ghazal of poetry? Some poet somewhere must have drawn the connection, and in that event I'll retract my remark on p. 67 of "Riddle of the Thread," my second work of literary theory. And that's the whole point of theory, as I understand it. If not the domain of things not yet known for certain, then theory's been misnamed.