Penelope at Mecca

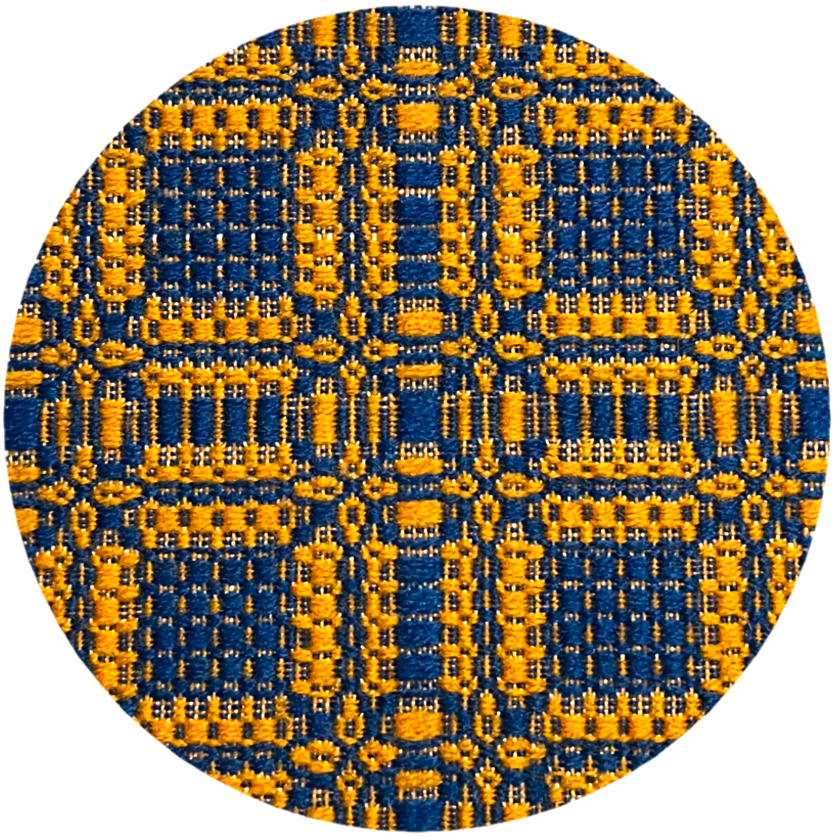

of the author's great aunt Laura Todd Burnell (1913–1999)

Six weeks ago, I attended a conference on Islamic art history at the University of York, and presented some research from the project I'm blogging here. A lot of my talk was about epic simile, which—much the way Homer likens battlefield exploits to humble trades like spinning and fishing, and various agricultural tasks—is the main context for representations of craft production in early Arabic poetry. And in the Q&A, the question came up: Is this coincidence, or is it a sign of Homer's reception and influence in Arabia of the Late Antique?

"I call it uncanny" was my first response, and this was inspired. The rest of my answer came out in a jumble that I'd like to reorganize here.

There is dynamism and pathos in repetitive manual labor, and through the magic of simile they are transferred to heroic gestae, playing on a social antithesis that anyone can appreciate. For these effects to be exploited in more than one literary tradition isn't cause for wonder, nor proof of influence. One example I love from Arabic poetry is the verse by Zuhayr (meter: basīṭ):

They fan their horses out on every battlefield,

like sparks thrown out at a blacksmith’s blow.

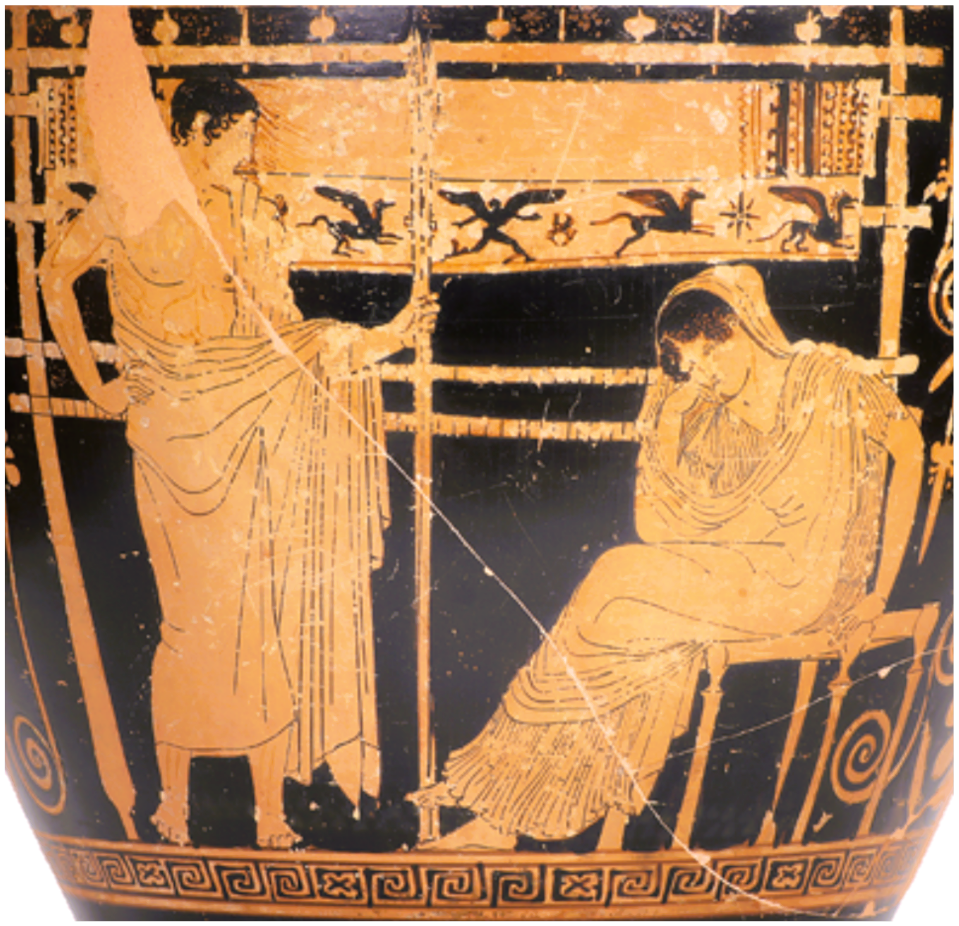

In the matter of textiles, one major difference between archaic Greek and Arabic tradition is the silence about domestic weaving that prevails in early Arabic poetry (as discussed in my previous installment). Meanwhile, the aristocratic heroines of Greek myth are consummate weavers, and this is too well known to call for examples.

For contrast, let me mention a couple of reports gleaned by al-Suyuti from Ibn ‘Asakir's History of Damascus, in which noblewomen are found spinning in their homes. "You, a governor's wife, are spinning?" the woman is asked in one version (no. 4345 in al-Tabarani), to which she responds: "I heard my father say: The Prophet, God's blessings and peace be upon him, said: 'Lengthen your thread and increase your reward. It chases Satan away, and causes ruminative thoughts to dissipate' (wa-yudhhibu ḥadīth al-nafs)." The report is charming, the hadith is beautiful, and I bring it up in order to underline the corresponding lack of praise for weaving in classical Arabic tradition, where it is consistently derogated as the work of enslaved people. And that is not at all how it was in archaic Greece.

Consider also this hadith: "Tailoring is excellent work for pious men, and spinning is excellent work for pious women." The craft that comes between spinning and tailoring is conspicuously left out. Although the hadith is judged noncanonical by most authorities, it is highly characteristic and symptomatic of tradition, where I wager that no aristocratic Arab woman can be found working at a loom.

ca. 550–530 BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Now for the uncanny. There is a Quranic verse that proclaims the sanctity of treaties, and rules out their dissolution once they are made. This is Sūrat al-Naḥl (The Bee) 16:92, and in making this injunction it resorts to an allegory that seems to come from Homer's Odyssey. Here let me quote the translation of Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall, slightly modified:

Be not like she who unravelleth her thread (ka-llatī naqaḍat ghazlahā), after she hath made it strong, to thin filaments, making your oaths a deceit between you because of one nation being more numerous than (another) nation. God only trieth you thereby, and He will explain to you on the Day of Resurrection that wherein ye differed.

Ibn Kathir says there are two schools of commentary on the verse. One is that the woman in question is an ad hoc metaphor for anyone who would "unravel" an agreement after swearing to it, and Ibn Kathir takes this view. The other is that there was an actual madwoman at Mecca who used to undo her threads after having spun them tight (al-Farra’ says her name was Rayta), and that the Quran's first hearers would have recognized the verse's reference to this individual.

As to the meaning of ghazl, Ibn Kathir has no comment, but Ibn al-Jawzi reports conflicting views. Majority opinion, he says, understands ghazl as nothing more than thread spun from cotton, wool, or hair. Then, there are those who take it for rope. And then he cites Ibn Qutayba's view that this woman would spin her thread, then weave it, and then unravel that weaving, reducing it to filaments. This is the interpretation one might have suspected all along—namely, that the madwoman's "thread" is a metonymy for her weaving, and that, rather than untwisting strands of thread, some woven thing is what she would unravel after having made it tight. Bringing us at last to Penelope's famous unweaving of the shroud on Ithaca, seemingly transplanted to Mecca of the seventh century CE.

ca. 450–400 BCE. Chiusi, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 63.564

Is it possible that Quran echoes Odyssey at 16:92? That depends on your definition of "echo." My definition would include Sūrat al-Kahf (The Cave) 18:60-63, where a bit from the end of the Gilgamesh epic appears in transmuted form. This is where Gilgamesh loses the sea-plant that restores youth, converted in Alexander Romance tradition into a story about testing the Fountain of Youth by dipping dried fish in it (and then losing the fish, which swims away, and losing track of the Fountain altogether), in which form it was re-transmuted (probably via the Syriac Song of Alexander of Pseudo-Jacob of Serugh) into a tale of Moses in Sūrat al-Kahf. This is what I call a legit echo, with an intertextual trail to back it up.

To my knowledge, no such trail leads from the poems of Homer to the Quran. I have seen a couple attempts to read Quran and Prophetic biography in generic terms of epic (1, 2), and these are interesting comparativist readings with little to say about true intertext. It's not impossible for Greek Epic Cycle material to have made it to Arabia—in the form of travelers' tales, say—and the legend of a woman who unravels by night what she weaves by day has what they call "legs." By that I mean it's memorable, portable, and adaptable, and that's as far as I'm willing to go in endorsing the Homeric echo of Sūrat al-Naḥl 16:92, i.e., not very. My word for it is still "uncanny."

For purposes of Hands at Work, the most important takeaway is the Quran's avoidance of words for weaving. Sūrat al-Naḥl 16:80 eulogizes tents and the raw material they are made of (wool from sheep and camels, and hair of goats), but actual weaving is nowhere mentioned. Nor does the namesake spider of Sūrat al-‘Ankabūt (The Spider) 29:41 weave her house, but ittakhadhat baytan: she "takes" it. This seems to parallel ghazlahā "her thread" at 16:92, where nasjahā "her weaving" would be the Penelopeian meaning, and in the view of Ibn Qutayba (who was no dummy) the true one.