Words that hint at flashing glimpses, and meanings that set captives free. Words like trees in flower, and meanings that inspire deep breaths. Words that borrow the sweetness of lovers' complaints, and crib from their tête-à-tête on the day of separation.

You'd think their words were pearls cascading from a cloud, if not purer drops in showers, whose meanings were pearls laced into a chain, only more precious. Language that is intimate and distant, provoking desires and dashing hopes, like the sun that brings light near while staying far above, and like water, so cheap when plentiful but costly when it runs out. Language that is easy for the astute to take in hand, and hard for everyone else. Language that ears will not reject and time will not wear away. Words that come as happy news gathered from a flower garden, and meanings like breaths of wind redolent of wine and aromatic herbs.

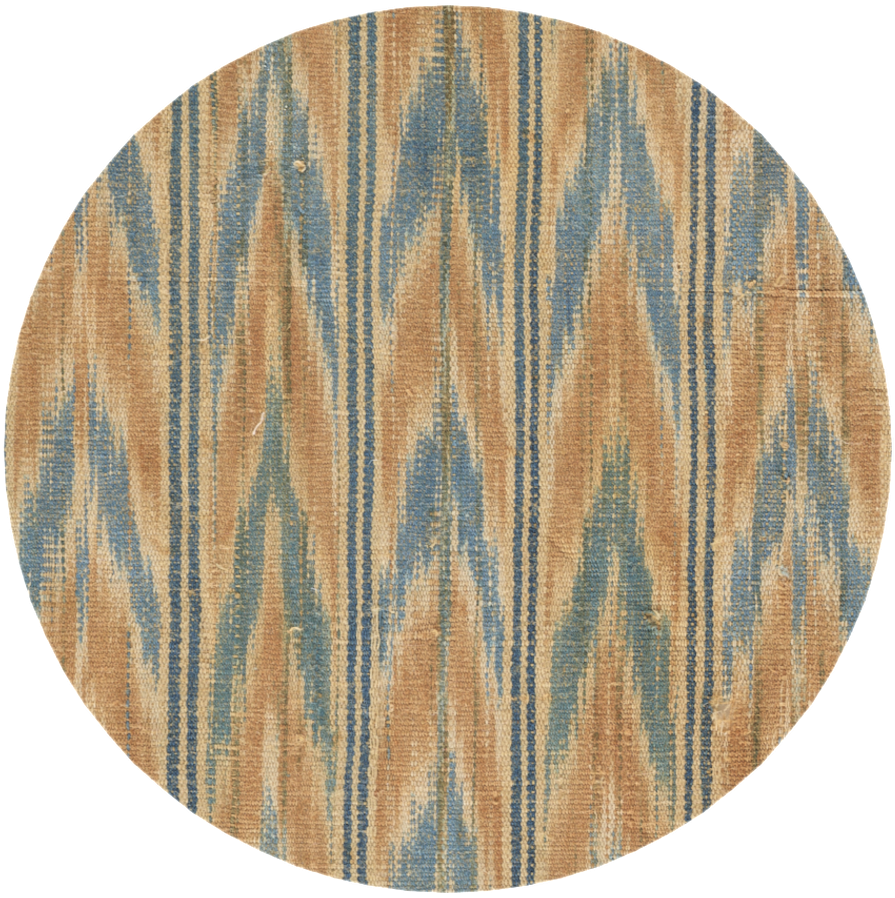

Smooth-flowing language of fine vintage mixed with rainwater, bringing realizations closer to its hearers. Witticisms that are magic portals, and nuggets like riches after poverty. Language like cooling drink on an overheated stomach, like prestige garments on an unbridled youth, full of highlights, supple contents, exquisite edges and non-abrasive surfaces. Language that is licit magic, cold springwater, and robes and mantles of resist-dyed weave, and apothegms and maxims and immanent happiness and blooming youth. I see in it the picture of pure refinement, and a paragon of excellence in its casting and molding. Words of coltish newness that are knots of ancient sorcery. Words that gladden the despondent, and level rugged ground, and make the treasured pearl an otiose thing.

Language that is free from affectation and far from blemish. Language with magic on its breath, and a smile of pearls in a row. Words whose golden surfaces inspire delight, and meanings whose verity overcomes the inborn temper. Words so tender-hearted, you'd think them copied from from a page of puppy love, but so ingratiating you'd think they were dictated by appetitive passion. Language that comes as an announcement of noble birth to the ear of sterile old age. Language that comes tantalizingly near and is forbiddingly remote, descending until it's just "two bow-lengths away, or even closer," then ascending until it is the highest thing that can be seen.

Language of beautiful brocade and subtle mixture, sweet to take in, cast without flaw, of enticing verbal makeup in which I read hidden meanings made plain, and words at close hand that hit faraway targets. If ever there were language that could melt boulders, cool embers, heal the sick and set aright the broken bone, this is it. His language seats its hearers on carpets, and courses through their hearts like resin in an aloe-tree. A man whose words are flowers, and his meanings fruits. His language is company for the settled, and provisions for the traveler. Language in which gazelles seek refuge, and sparrows bathe their wings. Language that emancipates clarity but keeps beauty in its thrall. Language that hauls in pearls, ties magic knots, dilates bosoms, and appeases Fate. Language whose range is far and its harvest nigh, inspiring affection in its hearers, and despair in [would-be imitators of] its craft.

From The Magic of Eloquence and the Secret of [Rhetorical] Expertise by

Abu Mansur al-Tha‘alibi