Chevrons

The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C.

It's worth repeating that texts are similar to textiles in many ways, and that no explanation of their likeness is wrong, least of all for artists, who can say what they feel. This overdetermination imposes the contrary of license onto historians. For historians, the surplus of analogies to be drawn between fiber art and language art should enforce skepticism, and the suspension of any connection that can't be demonstrated in the linguistic, poetic and material evidence of a given time and place, lest bare intuition substitute for cultural data.

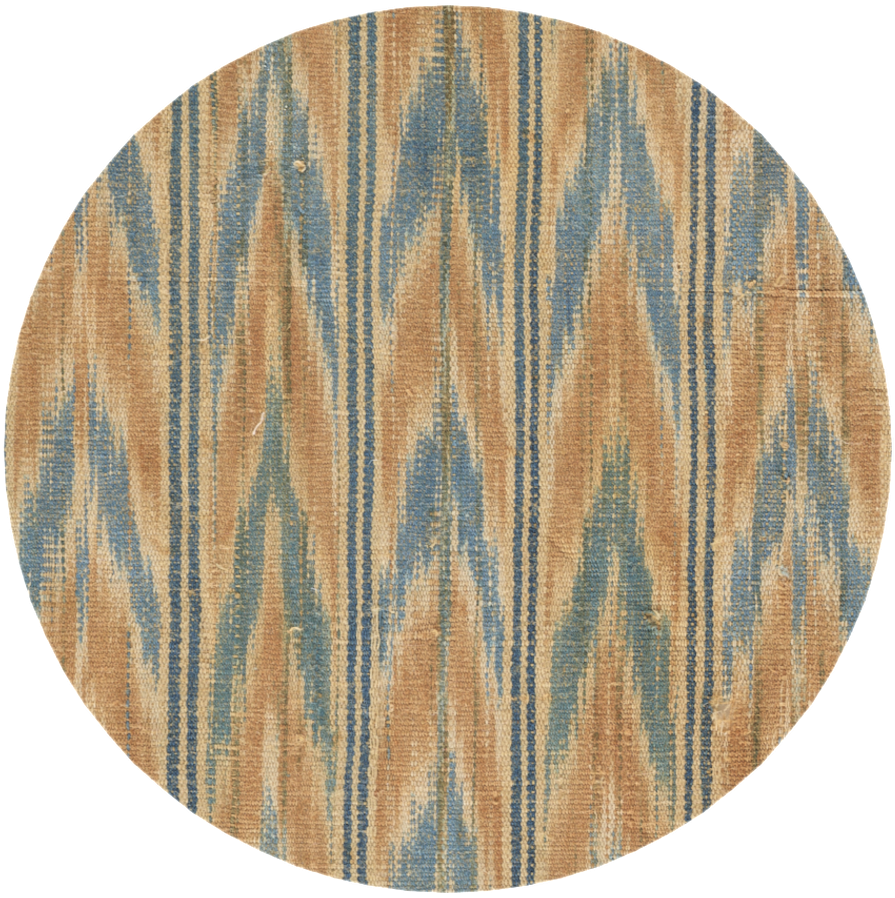

I will demonstrate this principle using the fabric called musahham, that is, "arrow-patterned." This was a style of weaving practiced in Yemen that I identify with a description by Ibn Abi al-Isbaʻ: "On a robe that is musahham, each arrow points to the next, its specific color determined by the aptness of its pairing with the color of the arrows before and after it." This well describes the textile fragment conserved at George Washington University's Textile Museum under accession number 73.466:

Dimensions: 34.92 x 37.46 cm (13¾" x 14¾")It also describes the the pattern called chevroned in English, from the French chevron meaning "rafter." Where two rafters meet under the ridge of a peaked roof, the angle of a chevron is formed. Herring-bone names it too, and in the textile vocabulary of English both terms are found. But the herring is a northern fish, and in traditional Arab architecture roofs are flat. So it is no wonder that in the textile vocabulary of Arabic, the head of an arrow (sahm) was made to serve instead.

Upon the medieval artifact's identification with the medieval description (unmade by anyone before this blog post, although I hinted at it on February 28) a different kind of scholar would dash into print. Naturally, I want full credit for identifying TM 73.466 as musahham weave, but for the purposes of Hands at Work, which is about the genealogy of weaving as a metaphor for poetry in Arabic, it's a collateral insight. Tashīm is not a metaphor, or any kind of figure of speech, but rather a syntactical achievement, observable in prose, poetry, and the verbal makeup of the Qur’an. And it is named after musahham weave. In al-Hatimi's Ornament of the Learned Gathering there is an uncelebrated passage that purports to give the origin of the poetic term:

I said to ‘Ali ibn Harun al-Munajjim (d. 352 A.H./963 CE), "I've never

seen a poet with better tashim than yours." "That's an idiom I came

up with myself," he said. "Tell me about it," I said. The answer he gave

described it uniquely, in terms borrowed from no one else:

Let me stop it there. You can dive into Ahmad Matlub's Dictionary of Rhetorical Terms if you're curious about the mysteries of tashim before my book comes out. The point here is that the poetic term's derivation from Arabic textile vocabulary is traceable to the first half of the 4th/10th century.

"And so," an essentializing critic might say, "yet again we see that Arabic poetry is a form of weaving." They wouldn't be wrong, as long as they don't retroject poetic tashim into the pre- and early Islamic periods, when musahham was a word for textiles only. The earliest mention known to me is by ‘Umar ibn Abi Rabi‘a (d. 93/712), where he describes "buxom lasses in sheer wrappers and musahham mantles of resist-dyed weave." And no amount of sophistry can construe this as a metapoetic image.

In fact, for all this poet's well-known delight in luxury garments, I have never found him to coin textile metaphors for his own versecraft. This owes at least partly to genre: early ghazal poetry (‘Umar's forte) is low on metapoetic self-reference relative to panegyric and invective poetry. It might also have something to do with the unique and uniquely troubling report that ‘Umar ran a shop at Mecca where seventy enslaved weavers were put to work. Perhaps weaving was too practical and prosaic a craft for ‘Umar to enlist in description of his own poetic art. Whatever the case, I bring him up as a caution against facile claims that Arabic poetry is always and everywhere represented as a form of weaving.

While renouncing essentialism is "best practice," it also means missing out on worthwhile intellectual adventures. Carl Schuster has very interesting things to say about chevron pattern as a primordial genealogical symbol ("a sort of female Tree of Jesse," he calls it), and where I read about chains of arrows as a means of celestial ascent in Neolithic rock art, I'm like "beam me up." Far, far be it from me to foreclose on the mystical semiotics of chevron pattern.

Nor do I presume to "intervene on" Art History as a discipline. I have much more to learn in this area than to teach. Having said that, let me also say that if historians of Islamic art realized how much information about material culture there is to be gained from early Arabic poetry—and only from early Arabic poetry—then they would spend more time reading it. They're definitely going to have to read Hands at Work.