August 1, 2023

June 30, 2023

The Bend in Arabic

[The verbs] i‘wajja, awida, māla, ḍali‘a, zawira, zāgha, ṣa‘ira, and ṣawira all mean the same. Ta’awwada is said of a thing that has a bend in it. And you say there is mayal in a bent thing, in addition to mayl, both verbal nouns of māla. [The nouns] ‘awaj, mayal, awad, ḍala‘, badan, zawar, zaygh, and ṣa‘ar are said especially for [affections of] the side of the face. God, be He Exalted and Magnified, says: Wa-lā tuṣa‘‘ir khaddaka li-n-nāsi "Twist not your cheek at people." Ṣawar and ṣayad are [upward bendings of a person's neck] from hauteur and pride, and [of a camel's neck] from the tugging of the rein upon the nose-ring.

From ‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn ‘Īsā al-Hamadhānī's Book of Words for Secretarial Use in Arabic Language Science, the recension of

Ibn Khalawayh

[The nouns] ‘awaj, awad, ḍala‘, mayal, zawar, zaygh, ḥinw, and ṣa‘ar are said especially for [affections of] the side of the face. Ṣawar and ṣayad are [upward bendings of the neck] from hauteur and pride. Mayal is for a bend in the formation of a thing, as is ḍala‘, and its affiliated verb is mayila yamyalu; mayl is for when you incline towards another, and its affiliated verb is māla yamīlu. One uses the verb ta’awwada of a thing, and i‘wajja, in‘āja, and in’āda when it bends. And while the "contortion" of an abstract matter is called ‘iwaj, the "bend" in a stick is called ‘awaj.

From ‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn ‘Īsā al-Hamadhānī's Book of Words for Identical and Similar Things, the recension of Abū 'l-Barakāt ‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Anbārī

tr. by David Larsen at 5:30 AM

Labels: Arabic lexicography

June 20, 2023

Interview With a Ampire

After thirty years in the arts, it's happened that someone asked me thoughtful questions about my work, and recorded and edited our conversation for everyone to enjoy. I will be forever grateful that it was my friend Tenaya Nasser-Frederick. Thanks also to the editors of Full Stop, where the interview appears in two parts: Part One | Part Two

UPDATED AUG. 31: Tenaya and I just gave no. 148 in the Brooklyn Rail's Wednesday reading series, and for better or worse the cloud recording's been made viewable until kingdom come. Thanks to Anselm and everyone at the Rail who makes it happen.

ALSO Gabriel Kruis's review of my new book Zeroes Were Hollow has appeared in the Poetry Project Newsletter 273 (Summer 2023), 27-8, and can be read right here. Thanks so much to Kay et alii at the Newsletter and ov course to Gabe.

AND NOW (DEC. 5): Jared Joseph's review of Zeroes appears as an insightful web-exclusive feature of Gulf Coast 36:1 (Summer/Fall 2023). Thanks to Jared, Gabriel and Tenaya, the book's launch is now complete, and I can go back to watching YouTubs.

Sly Stone on Dick Cavett (ABC, 1970)

Van Halen, "I'll Wait" (1984), fan video

AC/DC, "Highway to Hell" (Paris, 1979)

Elton John, "I Guess That's Why They Call It the

Blues" (Las Vegas, 2012), feat. Jean Witherspoon

tr. by David Larsen at 2:39 PM

Labels: Announcements

June 16, 2023

Man and crow

Abu 'l-Nashnash was a bandit of the Banu Tamim, an antisocial type and nuisance of the road who used to hold up caravans between the Hijaz and Syria. He was caught by one of Marwan's brigadiers, who fettered him and kept him prisoner, until Abu 'l-Nashnash took advantage of his captors' inattention and ran for it. He went along until he came to where a crow in a moringa tree was croaking and preening its feathers, and this filled him with disquiet. Then he came upon a group of the Banu Lihb, and said: "Ordeals and evils, imprisonment and dire straits—this man's been through them all, and escaped!" He looked to his right, and saw nothing. Then he looked to his left, and saw again the crow in a tree, croaking and preening its feathers.

"If the omen doesn't lie, this man's headed back to prison," a Lihbite said, "to languish in fetters until he's executed and exposed on a cross." "Suck a rock," said Abu 'l-Nashnash. "Suck it yourself," said the Lihbite. To which Abu 'l-Nashnash recited (meter: ṭawīl):

Many women ask where I'm headed, and many men.

Why ask the irregular where he's bound?

The broad highway, that's where. If someone hangs onto

what they'd better hand over, that's when I come near.

A lonely man who can't roam free and easy,

and no one is happy to see,

is better off dead than hovering

in penury around his master's well.

The open waste where the sandgrouse falters

is where Abu 'l-Nashnash comes riding through,

to avenge someone's killing, or take someone's stuff.

Is the prodigy not now in view?

He lies down to worse poverty, finding nothing he seeks

on darker nights than I've ever seen.

Live lawless or die noble. I have found no one

left behind that death came seeking.

From the Book of Songs

tr. by David Larsen at 1:08 PM

Labels: Arabic prose

June 9, 2023

Words and meanings

Words that hint at flashing glimpses, and meanings that set captives free. Words like trees in flower, and meanings that inspire deep breaths. Words that borrow the sweetness of lovers' complaints, and crib from their tête-à-tête on the day of separation.

You'd think their words were pearls cascading from a cloud, if not purer drops in showers, whose meanings were pearls laced into a chain, only more precious. Language that is intimate and distant, provoking desires and dashing hopes, like the sun that brings light near while staying far above, and like water, so cheap when plentiful but costly when it runs out. Language that is easy for the astute to take in hand, and hard for everyone else. Language that ears will not reject and time will not wear away. Words that come as happy news gathered from a flower garden, and meanings like breaths of wind redolent of wine and aromatic herbs.

Smooth-flowing language of fine vintage mixed with rainwater, bringing realizations closer to its hearers. Witticisms that are magic portals, and nuggets like riches after poverty. Language like cooling drink on an overheated stomach, like prestige garments on an unbridled youth, full of highlights, supple contents, exquisite edges and non-abrasive surfaces. Language that is licit magic, cold springwater, and robes and mantles of resist-dyed weave, and apothegms and maxims and immanent happiness and blooming youth. I see in it the picture of pure refinement, and a paragon of excellence in its casting and molding. Words of coltish newness that are knots of ancient sorcery. Words that gladden the despondent, and level rugged ground, and make the treasured pearl an otiose thing.

Language that is free from affectation and far from blemish. Language with magic on its breath, and a smile of pearls in a row. Words whose golden surfaces inspire delight, and meanings whose verity overcomes the inborn temper. Words so tender-hearted, you'd think them copied from from a page of puppy love, but so ingratiating you'd think they were dictated by appetitive passion. Language that comes as an announcement of noble birth to the ear of sterile old age. Language that comes tantalizingly near and is forbiddingly remote, descending until it's just "two bow-lengths away, or even closer," then ascending until it is the highest thing that can be seen.

Language of beautiful brocade and subtle mixture, sweet to take in, cast without flaw, of enticing verbal makeup in which I read hidden meanings made plain, and words at close hand that hit faraway targets. If ever there were language that could melt boulders, cool embers, heal the sick and set aright the broken bone, this is it. His language seats its hearers on carpets, and courses through their hearts like resin in an aloe-tree. A man whose words are flowers, and his meanings fruits. His language is company for the settled, and provisions for the traveler. Language in which gazelles seek refuge, and sparrows bathe their wings. Language that emancipates clarity but keeps beauty in its thrall. Language that hauls in pearls, ties magic knots, dilates bosoms, and appeases Fate. Language whose range is far and its harvest nigh, inspiring affection in its hearers, and despair in [would-be imitators of] its craft.

From The Magic of Eloquence and the Secret of [Rhetorical] Expertise by

Abu Mansur al-Tha‘alibi

tr. by David Larsen at 7:17 AM

Labels: Arabic prose

May 30, 2023

Avant ‘Udhra

In the land of the Banu ‘Udhra, I saw an aged man whose body was drawn in on itself like a bird's. I asked the woman attending him who this was. "It's ‘Urwa," she told me. So I bent down close and asked him, "Does your love affect you still?" He said (meter: ṭawīl):

My gut is like a wingèd grouse of the sands,

so very sharply does it flutter.

I went round to his left side, and he repeated the verse until I'd heard it from him four times.

I was sent as tax collector to the Banu ‘Udhra, and went about collecting their taxes until, when I thought I had passed beyond their territory, a threadbare tent came into view. Lying in front of it was a young man reduced to skin and bones. On hearing my tread, he began to chant in a weak and mournful voice (meter: ṭawīl):

To the healer of al-Yamama I'll pay what's due,

and to the healer of Hajr—but first they must heal me.

Just then, a rustling came from the tent, and inside it I beheld an old woman. "Old woman," I said, "come out, for this young man has passed the point of death, in my estimation." "Mine too," she said. "I haven't heard so much as a whimper from him in over a year, except these verses lamenting his departed soul" (meter: basīṭ):

Mothers weep forever. Who weeps for me

today? Now I am the one being subtracted.

Today they let me hear it, but when I uplifted

the people that I met, I heard nothing.

She came out and lo, the man had died. So I wrapped him in a shroud and prayed over him. I asked, "Who was he?" She said, "This is ‘Urwa ibn Hizam, the man slain by love."

From Abu ‘Abd Allah al-Yazidi's recension of the Poetry of ‘Urwa ibn Hizam; cf. Poetry and Poets, the Book of Songs, the Meadows of Gold, and The Tribulations of Impassioned Lovers

tr. by David Larsen at 12:29 PM

Labels: Arabic poetry

May 24, 2023

Alexander the Sleepless XVIII

I will narrate another miracle, supernatural and superhuman, about a medicinal brew the foresightful blessed one prepared for some brothers who were sick. For this purpose, they took ramekins of clay and set them in the ground [near the hearth] to be heated there, and he tapped four brothers to oversee the preparation in day-long shifts. Then there came a day when it slipped their minds—or rather, the Lord allowed it to slip their minds, in order that His servant stand revealed to all.

It was a day when no one paid attention. All they did with the ramekins that morning was to wash them, fill them with cold water and leave them sitting there. But when the hour drew nigh, and they were reminded of their duty, they were ashamed to look at any of their brothers, and did not dare to go to their abbot and let him know. Finally, one of them got up the courage, and went to him and said, "We had no wood, and heated no water." The blessed one, when he heard this, said, "And why were you not mindful of it this morning? Not that it matters: I know you're trying to test me. You can go back now, your water's hot." Doubtful as they were, they went back and found the ramekins bubbling, though it was obvious no fire had gone beneath them that whole day. And once again, the brothers marveled at the man's faith.

These few miracles have been chosen in order that we may believe in the many I could set forth, and that all things were possible for him through his perfect faith.

The Life of Alexander the Sleepless III.47

tr. by David Larsen at 3:51 PM

Labels: Greek prose , Vita Alexandri Acœmeti

May 17, 2023

Alexander the Sleepless XVII

Certain faithless men took it in hand to test his grace. Day and night, they shadowed the brothers to find out where their food was coming from, for every day they saw it ready, and that after taking what sufficed them, these slaves of God took no thought for the morrow, but gave it in abundance to the poor. Through the Holy Spirit, the blessed one knew of their investigation, and at a time when none had knocked upon their door, said to one of his followers, "Go, and let in what the Lord has sent us." And before the brother got there, a man in white came knocking. The brother opened it to find a basket full of fresh-baked bread, still warm—but the angel of God who had knocked so urgently was nowhere to be seen, leaving a man standing there with the bread. "Who sent you?" the brother asked when he came in. The man responded, "I was taking my loaves out of the oven when a man of giant size appeared beside me, robed in white, and fiercely pressured me to 'Take all that bread to the slaves of the Most High!' He made me follow him to this place, knocked on the door, and then he vanished. I don't even know where I am."

Hearing all this, the brother reported it to his blessed abbot. The holy Alexander received the bread and served it warm to the brothers, who were already at their tables. With gratitude, they took their share and gave the rest to their brothers, the indigent poor. And [those formerly faithless men] marveled when they saw the unrestrained liberality of him who, in accordance with Scripture, gave no thought to the morrow.

The Life of Alexander the Sleepless III.45

tr. by David Larsen at 12:54 AM

Labels: Greek prose , Vita Alexandri Acœmeti

May 7, 2023

What could this be?

The now-sainted Symeon was ailing at this time, and on the point of death. Gregory, when I made this known, sped to him, hoping to embrace him at the very end, but did not make it soon enough.

There were none to overshadow Symeon's greatness in his day. From the time he was a boy of tender nails, he pursued a life of hard extremity at the top of a pillar. His baby teeth had not yet fallen out when he took his stand there. The circumstances of his ascent to the pillar were these:

He was just a little kid, wandering boyishly in the foothills, when he came upon a wild leopard. Throwing his belt around its neck, he used the strap to lead around the beast, now forgetful of its wildness, and walked it back to his schoolhouse. Beholding this from the top of his own pillar, the schoolmaster asked: τί ἂν εἴη τοῦτο? "It's a cat," the boy said.

This proved the lad's future greatness, as far as the old man was concerned, and he conducted him up the pillar, where Symenon lived out sixty-eight years—first on that one, and then atop another in the highest fastness of the mountain. For expelling demons and healing every malady, every grace was due him, and for seeing into future things to come. To Gregory, he foretold that Gregory would not be present at his death. As to what might happen after that, he said, he had no knowledge.

From the Ecclesiastical History (VI.23) of Evagrius Scholasticus

tr. by David Larsen at 2:27 PM

Labels: Greek prose

April 23, 2023

Good neighbor

These verses were composed by al-‘Arji during his imprisonment

and made into a song (meter: wāfir):

They have forsaken me. What a hero they forsake!

One for days of battle and frontier outposts

and fatal clashes, standing fast

where heads of spears aim for my slaughter.

Now daily I am hauled about in manacles,

begging God's aid against wrongful restraint.

As if respect and honor were not conferred through me,

the scion of ‘Amr [who was a caliph's son]!

al-Bahili that al-Asma‘i said:

Abu Hanifa had a neighbor in Kufa who could sing. He used come home drunk and singing to his room on an upper floor, from which Abu Hanifa enjoyed hearing his voice. And very often what he sang was:

They have forsaken me. What a hero they forsake!

One for days of battle and frontier outposts...

One night, this man crossed paths with the vice patrol, who seized him and put him in prison. Abu Hanifa missed hearing his voice that night, and made inquiries the next morning. On hearing the news, he called for his black robe and high peaked cap and put them on, and rode to see [the governor of Kufa, who was] ‘Isa ibn Musa. He told him, "I have a neighbor who was seized and imprisoned by the vice patrol yesterday, and virtue is all I know of him."

"Bring out everyone detained yesterday by vice patrol, and let them greet Abu Hanifa," said ‘Isa. When the man was brought forth, Abu Hanifa called out, "That's him!"

In private he said to his neighbor, "Young man, aren't you in the habit of singing every night:

'They have forsaken me. What a hero they forsake'?

"Now tell me: have I forsaken you?"

"By God, your honor, no," the young man said. "You've been kind and noble. May God reward you handsomely!"

"You can go back to your singing," said Abu Hanifa. "It was congenial to me, and I see no harm in it."

"I will!" the young hero said.

From the Book of Songs

tr. by David Larsen at 6:11 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry , Arabic prose

April 14, 2023

Calligrapher unknown

"And He taught Adam all the names…" The Noble Qur’an (2:31)

"In reality, it is not images of objects but schemata that ground our pure sensible concepts. No image of a triangle would ever be adequate to the concept of it... The schema of the triangle can never exist anywhere except in thought, and signifies a rule of the synthesis of the imagination with regard to pure shapes in space…. The concept of a dog signifies a rule in accordance with which my imagination can specify the shape of a four-footed animal in general, without being restricted to any simple particular shape…" Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (A 141/B 180), tr. Guyer and Wood

Rear cover of al-Muṣṭalaḥ al-naqdī fī «Naqd al-shi‘r»

(Literary-critical Vocabulary in the Naqd al-shi‘r of

Qudama ibn Ja‘far) by Idris al-Naquri. Casablanca:

Dar al-Nashr al-Maghribiyya, 1982.

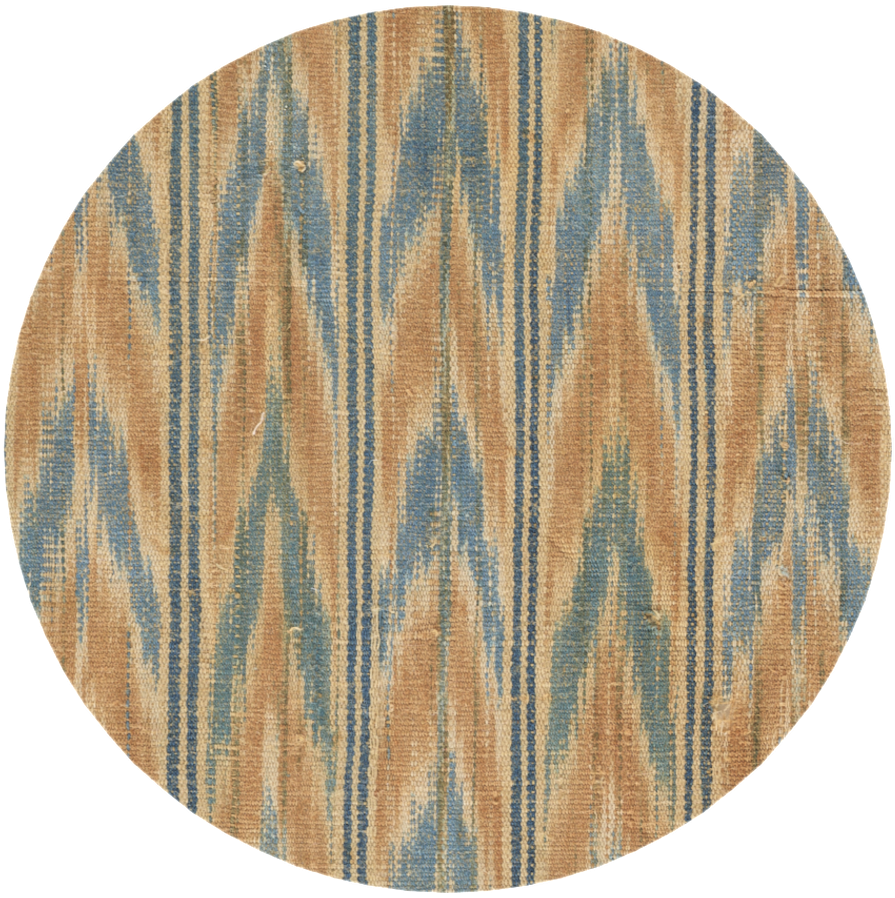

Chevrons

The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C.

It's worth repeating that texts are similar to textiles in many ways, and that no explanation of their likeness is wrong, least of all for artists, who can say what they feel. This overdetermination imposes the contrary of license onto historians. For historians, the surplus of analogies to be drawn between fiber art and language art should enforce skepticism, and the suspension of any connection that can't be demonstrated in the linguistic, poetic and material evidence of a given time and place, lest bare intuition substitute for cultural data.

I will demonstrate this principle using the fabric called musahham, that is, "arrow-patterned." This was a style of weaving practiced in Yemen that I identify with a description by Ibn Abi al-Isbaʻ: "On a robe that is musahham, each arrow points to the next, its specific color determined by the aptness of its pairing with the color of the arrows before and after it." This well describes the textile fragment conserved at George Washington University's Textile Museum under accession number 73.466:

Dimensions: 34.92 x 37.46 cm (13¾" x 14¾")It also describes the the pattern called chevroned in English, from the French chevron meaning "rafter." Where two rafters meet under the ridge of a peaked roof, the angle of a chevron is formed. Herring-bone names it too, and in the textile vocabulary of English both terms are found. But the herring is a northern fish, and in traditional Arab architecture roofs are flat. So it is no wonder that in the textile vocabulary of Arabic, the head of an arrow (sahm) was made to serve instead.

Upon the medieval artifact's identification with the medieval description (unmade by anyone before this blog post, although I hinted at it on February 28) a different kind of scholar would dash into print. Naturally, I want full credit for identifying TM 73.466 as musahham weave, but for the purposes of Hands at Work, which is about the genealogy of weaving as a metaphor for poetry in Arabic, it's a collateral insight. Tashīm is not a metaphor, or any kind of figure of speech, but rather a syntactical achievement, observable in prose, poetry, and the verbal makeup of the Qur’an. And it is named after musahham weave. In al-Hatimi's Ornament of the Learned Gathering there is an uncelebrated passage that purports to give the origin of the poetic term:

I said to ‘Ali ibn Harun al-Munajjim (d. 352 A.H./963 CE), "I've never

seen a poet with better tashim than yours." "That's an idiom I came

up with myself," he said. "Tell me about it," I said. The answer he gave

described it uniquely, in terms borrowed from no one else:

Let me stop it there. You can dive into Ahmad Matlub's Dictionary of Rhetorical Terms if you're curious about the mysteries of tashim before my book comes out. The point here is that the poetic term's derivation from Arabic textile vocabulary is traceable to the first half of the 4th/10th century.

"And so," an essentializing critic might say, "yet again we see that Arabic poetry is a form of weaving." They wouldn't be wrong, as long as they don't retroject poetic tashim into the pre- and early Islamic periods, when musahham was a word for textiles only. The earliest mention known to me is by ‘Umar ibn Abi Rabi‘a (d. 93/712), where he describes "buxom lasses in sheer wrappers and musahham mantles of resist-dyed weave." And no amount of sophistry can construe this as a metapoetic image.

In fact, for all this poet's well-known delight in luxury garments, I have never found him to coin textile metaphors for his own versecraft. This owes at least partly to genre: early ghazal poetry (‘Umar's forte) is low on metapoetic self-reference relative to panegyric and invective poetry. It might also have something to do with the unique and uniquely troubling report that ‘Umar ran a shop at Mecca where seventy enslaved weavers were put to work. Perhaps weaving was too practical and prosaic a craft for ‘Umar to enlist in description of his own poetic art. Whatever the case, I bring him up as a caution against facile claims that Arabic poetry is always and everywhere represented as a form of weaving.

While renouncing essentialism is "best practice," it also means missing out on worthwhile intellectual adventures. Carl Schuster has very interesting things to say about chevron pattern as a primordial genealogical symbol ("a sort of female Tree of Jesse," he calls it), and where I read about chains of arrows as a means of celestial ascent in Neolithic rock art, I'm like "beam me up." Far, far be it from me to foreclose on the mystical semiotics of chevron pattern.

Nor do I presume to "intervene on" Art History as a discipline. I have much more to learn in this area than to teach. Having said that, let me also say that if historians of Islamic art realized how much information about material culture there is to be gained from early Arabic poetry—and only from early Arabic poetry—then they would spend more time reading it. They're definitely going to have to read Hands at Work.

tr. by David Larsen at 7:40 AM

Labels: Hands at Work

April 8, 2023

Controversy of the sandals

"You have gone grey before your time," they said.

I said, "What greys my head is fear of earthquakes!

Scalps whiten at the wrong you do to Taybah,

and Radwa shakes, and the peaky mountains tremble."

They said, "Black sandals are for Christians."

"Then they follow the example of our Prophet,"

I replied. "But the lot of you are clad in error,

shod in what protects old ladies' feet.

Red sandals are for women of the Maghreb,

and in the East, yellow ones go with a trailing hem."

"Ahmad in black sandals?" they protested.

"This contrarian is sore confused."

"What are the sandals that I wear among you?"

I said. "Now put aside this fruitless strife."

"But Ali dressed in yellow," they said.

I said, "That Companion has naught to do with this."

They said, "Oral and written tradition are in agreement:

The Messenger's sandals were not the black of kohl,"

"Pray tell," I asked, "what color were they, then?"

Their answer to my question was "I do not know."

"Do intelligent people deny what's well established,"

I asked, "trespassing into what they're ignorant of?

I marvel at such claims. They're based entirely

on ways and means of tradition that are depraved.

So many askers have I told about his sandals:

'As to their blackness, my tradition is the road of roads.'"

"Might you enlighten us," they said, "to this tradition?"

I said, "Might I enlighten someone who's not a fool?

Black was the color of the Messenger's sandals." To which,

like ignorami who think they know a thing or two,

they objected, and spoke against the truth in sight of God,

and every mortal being from high to low.

They broke the staff of Islam, rejecting sunna,

and shredded centuries' worth of scholarly consensus.

So I fought them until, fearing for their buttress,

they slunk in shame and repentance to their homes.

Helpless before the rampant lion of knowledge,

they wrung their hands after their overthrow at mine.

For I schooled them in the truth until they learned it,

while they slept on it like idiots who drool.

I schooled them in the truth until they learned it,

whose education was a kitchen mule's.

I schooled them in the truth until they learned it,

who were no better trained than hyena pups.

I schooled them in the truth until they learned it,

and voided the vain humbug of their views.

I strung pearls of truth and knowledge for safekeeping,

and hung it round their necks devoid of truth,

and guided them like lambs without a shepherd

out of straying, clear of error, to the truth.

Verses 22-46 of a 131-verse invective poem (meter: ṭawīl)

by Muhammad Mahmud al-Turkuzi al-Shinqiti,

dated 1307 A.H. (1889-90 CE)

With thanks to Zekeria Ahmed Salem

tr. by David Larsen at 10:15 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry

April 1, 2023

No two hearts

Mujahid said: "'God does not put two hearts in one man's bosom' was revealed concerning a man of Quraysh who claimed to have two hearts, as a boast of of his mental abilities. He used to say, 'In my bosom, there are two hearts, and each one of them has more intellectual capacity than Muhammad.' This man was from the Banu Fihr."

Al-Wahidi, al-Qushayri, and others say: "This was revealed concerning Jamil ibn Ma‘mar al-Fihri, a man of prodigious memory for everything he heard. 'Anyone who can remember so many things must have two hearts,' said the Quraysh. 'I have two hearts,' he used to say, 'both of which have more intellectual capacity than Muhammad.'

"Jamil ibn Ma‘mar was with the idolaters at the battle of Badr when they were put to flight. Abu Sufyan saw him mounted on an ass, with one sandal fastened to his hand and the other to his foot. 'How's the battle going?' he asked him. 'Our people have been put to flight,' Jamil said. 'So why do you have one sandal on your hand and the other on your foot?' asked Abu Sufyan. 'I thought they were both on my feet,' said Jamil. And so his absent-mindedness was discovered, for all that he had two hearts."

Al-Suhayli said: "Jamil ibn Ma‘mar al-Jumahi was the son of Ma‘mar ibn Habib ibn Wahb ibn Hudhafa ibn Jumah—Jumah who was also called Taym. He claimed to have two hearts, and it was concerning him that the Qur’anic verse was revealed. He is also mentioned in this verse of poetry (meter: ṭawīl):

How will I abide in Medina, after

Jamil ibn Ma‘mar seeks it no more?"

From al-Qurtubi's Comprehensive Judgments of the Quran

tr. by David Larsen at 9:45 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry , Arabic prose