A Poem Is a Mantle

of Resist-Dyed Weave

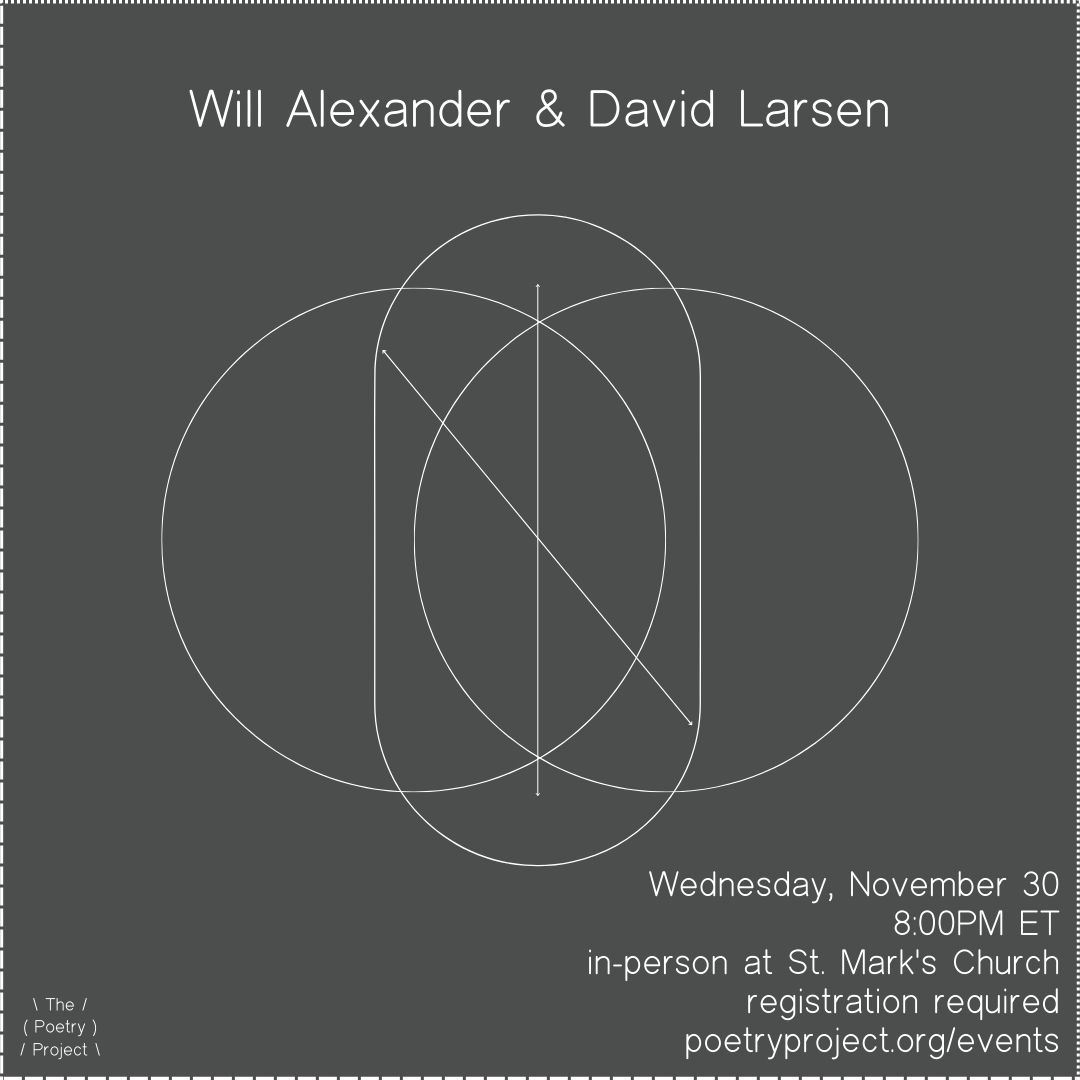

Yemen, 9th-10th centuries CE. Cooper Hewitt Museum

In how many ways is a poem like a robe? Don't make me count them. Whatever answer works for you intuitively is probably fine. For instance, texts and woven things are alike the products of cumulative effort—a likeness with no basis in etymology, history of technology, or any domain but practical experience to prove that it is so. You could call it a truism, or an apothegm, or (why not) a universal truth.

In early Arabic poetry, the analogy is not so multivalent. It is under specific circumstances that Arab poets of the 6th-8th centuries CE compare their work to textile craft, and to a specific textile form. Let me tell you about it, after answering one "so what" question that makes this more than a matter of antiquarian curiosity.

Since the 9th century, Arabic prose writers have been eloquent about the ways in which poetry is a craft like weaving (nasj) or the ordering of pearls on a string (naẓm), to the point that nasj and naẓm became synonymous with poetry itself (shi‘r). I don't like to say this is "well known," but it is comparatively well studied since Abdelfattah Kilito's 1979 article. Meanwhile, what the poets actually said about their poetry, in their poetry—the boasts they made of it and the similes they coined for it—is mostly ignored, and a lot of important social information along with it. What effects did the

poets think they were accomplishing through their work? That information is available, if you read what they say about their poetry, and what they compare their poetry to.

Take fabrics. Early Arab poets mention different types of cloth imported from different places (Egypt, Syria, Persia), and very rarely Arabian homespun. But when they say their poem is like a robe, it is a specific type of weaving that they reference: a striped cotton mantle made in Yemen of resist-dyed weave (a forerunner of Indonesian ikat). In collections in the US and Canada there are examples dating to the 9th and 10th centuries, many with bands of pseudo-Kufic writing in gold leaf (as pictured here).

This style of weaving is mentioned in an enigmatic verse by Aws ibn Ḥajar, a poet of the sixth and early seventh century (meter: ṭawīl):

When people rush at me in angry temper

I deck them out, marking them with fine, striped raiment

(kasawtuhumu min ḥabri bazzin mutaḥḥami).

I say the verse is "enigmatic" because it appeared in an anthology of enigmatic verses by Ibn Qutayba, who glossed it like this:

"Mutaḥḥam (striped) is an epithet of the garment he makes out to be al-atḥamī, which is a variety of Yemeni mantle. 'I deck them out in the very best of that type of garment,' he says. But this is a similitude, meaning 'I besmirch them in verse, and [the effect] is as evident as if they went dressed in these garments.'"

In other words, Aws is not talking about donations of fine clothes (as Geyer thought). He is saying that the object of his invective versecraft is marked out and made conspicuous, as if by an attention-getting robe. The atḥamī robe is defined by al-Aṣma‘ī as "a resist-dyed mantle of Yemen without embroidery," looking maybe like the ikat fragment pictured here.

The true keyword of Aws's verse is ḥabr. Dedicated readers of early Arabic poetry are well acquainted with cognates of this word, which name the genre of Yemeni mantle that atḥamī weave belongs to. Historians of Islamic art know the stuff too (see Vera-Simone Schulz, "Crossroads of Cloth," for references), but between resist-dye weave as material artifact and poetic signifier the correlation has been made by exactly no one until this blog post. When it is laid out in Hands at Work, the reader will gain access to something rare, and that is the chance to envision early Arabic poetry as it was conceived and represented by the poets themselves.