May 18, 2019

May 12, 2019

Sheep for sheep

Al-‘Ajjaj came to me and asked, "Would you accept a ewe lamb in exchange for another sheep that answers my description?"

"What is your description?" I said.

"Not much hair in the front, but lots of hair in back. From the front, you'd think it was a goat, but from behind you can tell it's a sheep."

I searched my flocks, and found one sheep answering his description, which I gave to him, and took his ewe lamb in exchange. I wouldn't have done this for just anyone - but this was al-‘Ajjaj, who might bring fame to my flocks!

From The Book of the Sheep by Al-Asma‘i

tr. by David Larsen at 10:45 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry , Arabic prose

April 26, 2019

Women who loved women

Names of [books about] elegant women who were lovers:

The Book of Rayhana and Qaranful (Basil and Clove)

The Book of Ruqayya and Khadija

The Book of Mu’yas and Dhakiya

The Book of Sukayna and al-Rubab

The Book of Ghatrifa and al-Dhalfa’

The Book of Hind and the Daughter of al-Nu'man

The Book of ‘Abda the Clever and ‘Abda the Fickle

The Book of Lu’lu’ and Shatira

The Book of Najda and Za‘um

The Book of Salma and Su‘ad

The Book of Sawab and Surur

The Book of al-Dahma’ and Ni‘ma

tr. by David Larsen at 9:58 AM

Labels: Arabic prose , Lost works

April 4, 2019

To the Graces

On spying Aristagoras, you the very Graces

flung your gentle arms around his darling person.

Thanks to you's the fire thrown off now by his frame, whether

sweet talking or making silence talk with just his eyes.

Keep him away from me? As if that would help! Like a new Zeus,

the boy knows how to make a bolt land far from Olympus.

tr. by David Larsen at 1:53 PM

Labels: Greek poetry

March 25, 2019

An imbecile from the Age of Ignorance

Another imbecile was ‘Ijl ibn Lujaym ibn Mus‘ab ibn ‘Ali ibn Bakr ibn Wa’il. One example of his idiocy is that when asked, "What do you call your horse?" he stood before it, put out one of its eyes and said, "I call him al-A‘war." And al-‘Anazi said (meter: tawil):

The Banu ‘Ijl accuse me of their patriarch's malady.

But what man was ever dumber than ‘Ijl?

It was their patriarch who made his steed half-blind, when

into a byword for idiocy he made their name.

From Reports of Imbeciles and Simpletons by Ibn al-Jawzi (Ibid).

tr. by David Larsen at 9:11 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry

March 9, 2019

If in Chicago

Image source: Composite drawing of Irtašduna's personal seal

by Margaret Cool Root and Mark B. Garrison, courtesy of the artists

and the Persepolis Seal Project. Colored pencils and gouache by LRSN

(2007 throwback)

tr. by David Larsen at 1:05 PM

Labels: Announcements

February 16, 2019

On the eve of al-Waqit

Abu ‘Ubayda said: This is what I was told by Firas ibn Khandaq.

Al-Lahazim ("The Middle Ranks") were [a tribal subgroup of Bakr ibn Wa’il, comprising the clans of] Qays and Taym Allah ibn Tha‘laba ibn ‘Ukaba, ‘Ijl ibn Lujaym, and ‘Anaza ibn Asad ibn Rabi‘a ibn Nizar.

On some pretext, the Lahazim held a gathering whose true purpose was to launch a raid on the Banu Tamim. Their movements were spotted by a man of Tamim held captive by the Banu Sa‘d of Qays ibn Tha‘laba. The captive hostage's name was Nashib ibn Bashama al-‘Anbari, called the One-Eyed (al-A‘war). He said to his captors: "Bring me a messenger, that I may instruct my family concerning some affairs of mine."

The Banu Sa‘d (who had purchased Nashib from the Banu Abi Rabi‘a ibn Dhahl ibn Shayban) feared that he would alert his tribe, and told him, "You may dispatch your message in our presence."

"Okay," he said. But when they brought him a lad belonging to no tribe of the Arabs, he objected: "You've brought me a simpleton!"

"By God," said the lad, "I am no simpleton."

"You're an idiot," said the One-Eyed, "I can tell."

"By God, there is nothing idiotic about me!" the lad said.

"Then which are there more of," the One-Eyed said, "stars or moons?"

"Stars," said the lad, "by a lot."

The One-Eyed filled his hand with grains of sand, and said, "What is the quantity in my hand?"

"I don't know," said the lad, "but I reckon it's a great many."

The One-Eyed pointed at the sun and said, "What is that?"

The lad said, "That's the sun."

"I see now that you are bright and clever," said Nashib. "Go to my family and communicate my greetings. Tell them to treat their hostage with kindness and generosity, since that is how my captors are treating me." (At this time, Hanzala ibn Tufayl al-Marthadi was in the hands of the ‘Anbaris.) "Tell them to unsaddle my red stallion and eqiuip my white mare, and see to my affairs among Malik's kids. Tell them the boxthorn is in leaf, and that the women are complaining. And tell them to ignore the commands of Hammam ibn Bashama, who is a no-good, marginal person, and to obey instead Hudhayl ibn al-Akhnas who is felicitous in judgement."

"Who are the kids of Malik?" asked the Banu Sa‘d.

"My nephews," said Nashib.

When the messenger reached Nashib's people and relayed to them the message, they were nonplussed. "This discourse is unknown to us," they said. "The One-Eyed must have lost his mind. We don't know anything about a mare belonging to him, nor a stallion. His whole herd is with him, as far as we know."

Then Hudhayl ibn al-Akhnas said to the messenger, "Tell it to me from the beginning," and the lad related all that the One-Eyed had said from beginning to end. "Go back and convey our greetings to him, and tell him we'll carry out his instructions." And the messenger departed.

"O ‘Anbar!" Hudhayl then cried, summoning the people. "Your comrade has expressed everything to you clearly. The sands in his hand are to make you know that a host of incalculable numbers is on its way. By pointing to the sun, he says that the danger is clearer than daylight. The red stallion he orders you to 'unsaddle' is the area of al-Summan, which he orders you to evacuate, and the white mare is al-Dahna’, which you are to fortify. And he orders you to warn the Banu Malik, and to bind them with an oath of mutual protection.

"The enemy host bristles with weapons, and those are the 'leaves on the boxthorn.' And the women's ishtika’ is [not 'complaint,' but] their crafting of shika’ - meaning 'water-skins' for the men to take on their raid!"

Nashib's people heeded the warning, and rode to al-Dahna’. They tried to alert the Banu Malik ibn Hanzala ibn Malik ibn Zayd Manat, who said, "We don't know what the Banu 'l-Ja‘ra’ are talking about." (This was their nickname for the Banu ‘Anbar. Ja‘ra’, like ja‘ari and jay‘ar, is the hyena.) "Their comrade's say-so is no cause for us to withdraw."

The Lahazim showed up the next morning to find the settlement abandoned, its people having fled. So they went to seek them out at al-Waqit.

From The Flytings of Jarir and al-Farazdaq by Abu ‘Ubayda

tr. by David Larsen at 1:12 PM

Labels: Arabic prose

January 18, 2019

An actor to the end

O Death, whom love of jest escapes - you who know nothing

of indulgence or happiness - what have I to do with you,

when these are what brought me my prestige, my world renown,

my income and my roomy house?

Ever was I full of cheer. If cheer give way

to mundane vagary and deception, what's the use?

When I was on the scene, the irate ceased their raging.

The acutely pained would laugh when I showed up.

Nagging cares were of no concern, and mischance

of fortune lost its power to disappoint.

The grip of every fear was broken by my presence,

and all times spent with me passed blessedly.

To see and hear me at work, even in a tragic role,

was a thrilling and consoling pleasure in more ways than one.

I put on my characters' faces, their manners and their words,

such that many seemed to speak out of one mouth.

Any man whose likeness I replicated for all to see

would shudder at himself magnified in my face.

And how many times did a woman behold my mimicry of her

gestures, and turn bright red, slain by shock!

However many the appearances my body was seen to take on,

so many are disappeared with me on an evil day.

Whereby with somber mien I am stirred to beg you now

that you read my inscription aloud in pious tones,

saying through your grief: "Happy as you were, O Vitalis,

may you be no less happy even now."

Epitaph of Vitalis, a mime of the fifth century

(San Sebastiano fuori le mura, Rome)

tr. by David Larsen at 12:27 PM

Labels: Latin poetry

December 30, 2018

November 24, 2018

A‘shā's pearl

Sleep is for the untroubled. I lie awake all night, unable to sleep

nor rise, shepherding the stars, my elbow for a pillow,

eyes propped open by anxiety, the malady that cancels slumber.

She went off with my heart and won't set it free.

If I don't see her then I won't get better. What healing

is there for the lovesick if she won't come near?

She ensnared my heart with the eyes of a doe that heeds

the squeak of her helpless newborn on the ground,

and the cool of her teeth in their orderly rows—as if

twice rinsed with camphor is their flavor—

and the untwitching neck of a white gazelle as it nibbles

leaves and berries from the arāk-tree,

and a haunch like a mound of sand, steep and curving.

No slim-hipped, girdled thing is she [whom I describe].

She's like the fair-hued pearl disembedded by a diver

who braves the depths of Dārīn where it lay.

From year to year he’s craved it, ever since his moustache sprouted.

Yearning agitates the diver in old age.

The desire of his soul is unremitting, and he flings [care for] it aside,

and when he catches sight of his desire, he burns for it.

The pearl is guarded by a jinn—a burly one who sets men amaze.

His eyes are open and he is on it.

Always mindful of the pearl, he circles it,

vigilant for thieves who prowl the deep,

coveting it. The pearl might surrender its enclosure

to a diver who risks drowning to obtain it!

Who craves the pearl in the whirl of the unfathomable is parted

from his life, and perishes beneath its heaving surface.

Who gains it gains eternity without end.

He is blessed and happy, and his satisfaction is complete.

That’s how she is. Your soul inflames your hope for her,

and you are ruined, and burnt is what you get.

tr. by David Larsen at 1:22 PM

Labels: Arabic poetry

September 8, 2018

Glass over gold

In one of his epistles, Sahl ibn Harun spoke in praise of glass to the detriment of gold:

Glass is a transparent substance that shares in light. It is better to drink from than any mineral or metal. It is not heavy in the hand, and does not conceal the drinker's face from his companions. Its price is nothing to haggle over.

Gold is a transient possession whose mere mention is a bad omen. One of its blameworthy properties is the speed with which it accrues to blameworthy people. It misleads all who keep it, and guards for them its venom. It is furthermore one of the Devil's snares, which is why they say: "Two red things are the ruin of men."*

Glass does not absorb grease, and grime does not stick to it. The only thing needed to wash it clean as new is water. Glass is of all things the most similar to water. As marvelous as are its properties, its manufacture is a marvel greater still.

From The Roving of the Eyes: A Commentary on the Comic Epistle of Ibn Zaydun by Ibn Nubata

*Gold and saffron. (Bywords for lucre and luxury, as in the saying of

Abu Bakr al-Siddiq.)

tr. by David Larsen at 10:10 AM

Labels: Arabic prose

August 29, 2018

Two personal announcements

ITEM ONE:

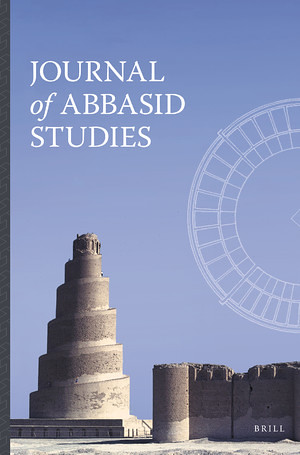

My article "Meaning and Captivity in Classical Arabic Philology" is on pages 177-228 of the Journal of Abbasid Studies 5:1/2 (2018). This article is Open Access, and available by clicking on the cover below.

ITEM TWO:

My translation of Ibn Khalawayh's Names of the Lion has received the 2018 Harold Morton Landon Translation Award. To the Academy of American Poets, and judge Ammiel Alcalay, thanks!

tr. by David Larsen at 10:11 AM

Labels: Announcements , Secondary literature

June 14, 2018

When the saints go marching out

By Abu Madyan Shu‘ayb al-Ghawth (meter: ṭawīl):

To You I surrendered my reason, my gaze, my hearing,

my spirit, my insides, and all of me altogether.

By astonishment at Your beauty I was waylaid

and, at sea in love's distraction, knew not my place.

When You put me under orders to keep your secret hid,

it came to light through the outpouring of my tears.

My endurance gave out. My resilience grew small.

Sleep and I parted ways, and my couch was barred to me.

Then I came before the Judge of Love and said: My [fellow] lovers

are harsh with me. "In love you are a vain pretender,"

is what they say.

But I have witnesses! To my sorrow and my ardor they will attest,

and you will hear the truth of what I pretend:

my sleeplessness, my suffering, my passion and dejection,

my pining away, my jaundiced pallor, and my tears.

It is a wonder and a marvel how I pine for their company.

Even in their company, my longing for them flares.

My eye weeps for them when they are at its black center,

and my heart bewails their estrangement, even as they

lodge between my ribs.

Whoever gives in to love's distraction and seeks me out

will find me among the poor, with nothing on me.

And whoever clamps me in jail, indulging their harshness,

will have me [nonetheless] for their intercessor.

Alternately attributed to Malik ibn al-Murahhal

tr. by David Larsen at 10:25 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry

March 22, 2018

Thirty Questions to the Moon

In times past, the Arabs couched their knowledge of the moon in the form of questions and answers about how each night of the month might be reckoned from its light, as well as other matters, saying:

The moon was asked: "O son of one night, what are you?"

"Milk of a ewe whose folk have camped in an arid quarter," said the moon. [A singsong reply that rhymes in Arabic with the asker's question, as do all the moon's replies up to night thirteen.]

"And on the second night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"Talk between two domestics [of different households], full of slander and untruth," said the moon.

"And on the third night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"Talk amongst a group of girls brought together from distant quarters," said the moon, and "of short duration" is added [to the moon's reply].

"And on the fourth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"The lapse of time a camel's calf goes between nursings," said the moon.

"And on the fifth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"Talk amongst intimates," said the moon.

"And on the sixth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

The moon said, "[I heed two commands:] 'Roam and stay.'"

The moon was asked, "On night seven, what are you?"

"The fattening of two calves," said the moon. "The hyena's ramble" is also said [to be the moon's reply].

"And on the eighth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"The lovers' moon," said the moon. "A loaf divided among brothers" is also said [to be the moon's reply].

"And on the ninth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"By my light, an onyx can be found," said the moon.

"And on the tenth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"I uphold the testimony of dawn," said the moon.

"And on the eleventh night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"By night and in the morning I am visible." said the moon.

"And on the twelfth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"A guarantor of night-travel," said the moon, "for townsfolk and nomads

alike."

The moon was asked, "On night thirteen, what are you?"

"A brilliant disk, dazzling to the viewer's eye," said the moon.

"And on the fourteenth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"My youth in full bloom, I shine through the clouds," said the moon.

"And on the fifteenth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"I am at my fullest, and my days dwindle," said the moon.

"And on the sixteenth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"Diminished in form, from east to west," said the moon.

"And on the seventeenth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"I am penury, the poor man's mount," said the moon.

"And on the eighteenth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"Evanescent," said the moon, "and fast to pass away."

The moon was asked, "On night nineteen, what are you?"

"From humility, I am slow to rise" said the moon.

"And on the twentieth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"I rise at dawn, and am visible when the day is young," said the moon.

"And on the twenty-first night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"My night-journey goes no further than my visibility."

"And on the twenty-second night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"The smudge of battle and the lion of war," said the moon.

"And on the twenty-third night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"In dark of night, I am lifted to a torch's height," said the moon.

"And on the twenty-fourth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"A mere fraction," said the moon, "whose rising leaves the darkness

undispelled."

The moon was asked, "On night twenty-five, what are you?"

"On nights like this, I'm neither disk nor crescent," said the moon.

"And on the twenty-sixth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"All hopes cut off, my end is due," said the moon.

"And on the twenty-seventh night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"I hug the earth, but shed no glow upon it," said the moon.

"And on the twenty-eighth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"An early riser. By midday I'm invisible," said the moon.

"And on the twenty-ninth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"Just ahead of the sun's rays, my stay is fleeting." said the moon.

"And on the thirtieth night, what are you?" the moon was asked.

"A crescent," said the moon, "for whom the way forward is the way down."

From the Meadows of Gold of al-Mas‘ūdī;

cf. the Book of Days and Nights and Months of al-Farrā’,

and Uncommon Vocabulary of Prophetic Narration by Ibn Qutayba

tr. by David Larsen at 2:09 PM

Labels: Arabic prose