I would not have missed the chance to work with this team of editors and translators for the world. Many thanks to Hatem Alzahrani and Bander Alharbi. This is my first commissioned translation. My fee went to Climeworks.

I would not have missed the chance to work with this team of editors and translators for the world. Many thanks to Hatem Alzahrani and Bander Alharbi. This is my first commissioned translation. My fee went to Climeworks.

tr. by David Larsen at 9:45 AM

Labels: Announcements , Arabic poetry

Marwan ibn Abi Hafsa was reciting his poems before my father. He said, "If I could add some of your verses to mine I would be rich." At this, my father invited his rhapsode to recite them. So he recited a poem of Bashshar's rhymed in lām, and, when he got to the verses (meter: ṭawīl)—

A depiction of you has been sent abroad by me.

Off [my poem] went, and did not fail to arrive at inhabited areas.

To the East and West I cast it, and the land swarmed

with its reciters and travelers [who recited it elsewhere]

—Marwan said, "O Abu Mu‘adh! [That is, Bashshar.] Other poets are storks, but you are a falcon."

And Muhammad ibn Yahya said:

Bashshar's verse was imitated by Muhammad ibn Hazim al-Bahili (meter: wāfir):

The meaning I intend forbids I make my poem long.

My expert sense of [formal] correctness does the same.

By making a short selection, and employing brevity,

I shall curtail the length of my answer,

and when I perform it for parties of travelers

rhapsodes and riders will say it back to one another.

From The Ornament of the Learned Gathering

by Abu ʿAli Muhammad al-Hatimi

tr. by David Larsen at 9:26 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry

by Ma‘qil ibn Dirar, called al-Shammakh

(floruit 1st half of the 1st century A.H.),

appears in issue 29 (2020) of A Public Space

وبالعربية ت صلاح الدين الهادي

Thanks to the editors

tr. by David Larsen at 9:48 AM

Labels: Announcements , Arabic poetry

Then he heard of a city ruled by activity of the Evil One, where adoration of idols was a non-stop festival and the people rejoiced in sacrilege. Alexander braced his loins with the preparation of the Gospel, charged up to their celebrated temple and set fire to it, and pulled it down with godlike power. The prize was his, nor did he decamp from it, but made his seat there in the temple.

The people of the place were apoplectic, and they raced up to put him to death, but at a blast of discourse from the man their tempers withered, and they retreated. The protecting grace of God was at work, as Alexander let out the apostolic cry: "I am a man who suffers as you do, and have wasted time like you on useless things. Flee eternal damnation. I recommend to you the kingdom of heaven." And things went on like this, and from all harms that they attempted the noble athlete was safe.

Then citizen Rabbula—a city father, thanks to his powers of wealth and rhetoric, who went on to become a denouncer of idols and a herald of the truth, but was then a raving idolater and a henchman of the Devil—addressed the mob in a loud voice: "Brothers! Fathers! Abandon we not the gods of our fathers, but let us complete our sacrifices according to tradition. The gods remain aloof from this Galilean who damages them. If they do not defend themselves, it is due to humanitarian reasons, or to the greatness of the Christians' god."

Encouraged by his mastery of the mob, and benighted by the Devil's every wile, Rabbula told them, "I shall go up to him by myself, and purge our temple of his magic and deceit, and right the wrongs he has done to our gods and to all of us." And he went up full of bluster, and engaged Alexander in dialogue. [....] He said, "I am eager to learn the full extent of your mania. What impels you to keep up this abuse of our gods? It has us dumbfounded."

The blessed Alexander heard his words, and said, "Listen to the power of our God and the mystery of our faith." He went on to speak of God's good will toward men, and the power of the holy scriptures, beginning from the creation of the universe up until the investiture of the cross. All that day and all that night, the dialogue went back and forth between them, and they kept themselves from food, and did not give themselves to sleep....

Rabbula chortled and said to the blessed Alexander, "If these things are true, and your God is, as you describe him, so attentive to his servants, then pray to him for fire to come down right in front of us. If that happens, I will declare that there is no god but the god of the Christians—since, as you say, you are his servant. But your scriptures are in truth falsehoods."

The blessed Alexander had no doubt that God would assent to his request, since it is written that "All things are possible to one who believes." He said to Rabbula, "Call on your gods, since there are so many of them, for fire to come down. I too will call on my god for fire to come down, and set alight the woven mats that lie before us."

"I lack the authority to do so," said Rabbula. "You go ahead."

At this, the holy Alexander arose, boiling over with the spirit, and said, "Let us pray." Facing east, with his hands outstretched, his prayer was such that Creation was set in motion, and fire came down and ignited the mats placed round the temple, just as the noble athlete had said. The men were unharmed, but Rabbula was overcome with wonder, and, thinking he would be ignited also, fell to the blessed Alexander's feet and did not let go until the fire had subsided, saying then in a loud voice: "Great is the god of the Christians!"

From The Life of Alexander the Sleepless (II.9-11, 12, 13)

tr. by David Larsen at 7:23 AM

Labels: Greek prose , Vita Alexandri Acœmeti

Alexander spent four years in Syria, fighting the good fight, and his progress in the Lord was substantial. Although he adhered to every rule, he remained keenly attentive to whether monastic life were lived in accordance with holy scripture, and found that it was not. As devotees well know, the renunciation of wealth and care for the future enjoined in holy Gospel is not maintained in cenobitic life, where it is someone's job to provide for the brothers and attend to their needs. But Alexander was a slave of God, boiling over with the Spirit, and the words of the Master—"Take therefore no thought for the morrow" and "Ye are of more value than many sparrows"—were forever in his ears, and his inner turmoil could not be contained. [....]

With the Holy Gospel in his hand, he strode up to the abbot and asked, "The things that are written in the Holy Gospel, father—are they true?"

Now Father Elias was a father indeed, and the shepherd of an inference-making flock, and on hearing the blurted question he surmised that the Evil One had led this brother away from faith. Straightaway he fell with his face to the floor, and said nothing to Alexander but called to the others, "Come pray for this one, who struggles in the Devil's trap!" And for two full hours all the brothers wailed over him, begging God for aid.

The abbot then got to his feet and said, "How comes this question to you, brother?"

Alexander was undeterred. "Are the things in the Holy Gospel true, or are they not?" he asked.

"Yes," they all replied, "because they are the words of God."

"Then why do we not carry them out?"

"Because no one is able to." they said.

At this, Alexander's outrage was unrestrained. To be cheated into wasting all that time! He took his leave of the entire community and, clutching the Holy Gospel, set out to follow what is written there in imitation of our holy fathers. Hereupon, the prophet Elijah became his model, and he made his home in the desert, where he spent the next seven years heedless of earthly cares, living as the Holy Spirit dictated.

From The Life of Alexander the Sleepless I.7, 8tr. by David Larsen at 6:22 PM

Labels: Greek prose , Vita Alexandri Acœmeti

The blessed Alexander was an Asiatic Greek from a noble family of the Aegean Islands. He studied the full course of literary sciences at Constantinople, and this was a complement to his moral education, which had developed his Christian piety and honest virtues to their full extent. His training complete, he entered government service, where he soon discovered how corruptible and fickle life is, and that "like a flower of grass" earthly glory too is fleeting. He came to despise his mundane existence and resolved upon a better way of way of life. He put the Old and New Testaments through rigorous philological inquiry, finding in the Gospels a treasure beyond assail for those who go forth trusting in the one who said: "If you want to be perfect, sell everything you have and give it to the poor, and your treasure will be laid up in heaven. Then come follow me."

When Alexander heard this, his conviction was total, and straightaway he took his share of inherited capital along with his earnings as prefect (an office he had discharged with fairness and nobility), a substantial sum, and gave it all to the poor and needy. His hope was then to isolate himself from friends, family and fatherland, and for Christ alone to be his intimate and lord. And he heard that communities of holy men were reverently pursuing this way of life in certain parts of Syria.

From The Life of Alexander the Sleepless (I.5-6)tr. by David Larsen at 4:00 PM

Labels: Greek prose , Vita Alexandri Acœmeti

Due to the utter insufficiency of words for this narration, all historians have kept their silence, which has been detrimental for those who wish to rise to his example. It is for their purposes that I—like traders who cheat death as they rove this world in quest of elusive gains—commit the rashness of setting down this account, seizing the present moment to give his would-be emulators the benefit of a partial description. For a fully proportionate description of this noble athlete's virtues is beyond human telling.

From The Life of Alexander the Sleepless (I.4) by Anonymous

tr. by David Larsen at 8:11 AM

Labels: Greek prose , Vita Alexandri Acœmeti

The Muwashshaha Qalandariyya of

Taqi al-Din ibn al-Maghribi (d. 1285)

appears in this month's Brooklyn Rail.

Thanks, Anselm

tr. by David Larsen at 10:48 PM

Labels: Announcements , Arabic poetry , Ibn al-Maghribi

I was told by Abu 'l-Qasim al-Juhani:

The caliph al-Muqtadir bi-'llah wanted to drink wine amid a bed of narcissus, in a small courtyard of the palace where there was a well-kept garden. One of the gardeners told him, "With narcissus, the trick is to fertilize them several days before your party, so they'll be nice and strong."

"Don't you dare!" the caliph said. "You would use manure on what I want to sit among and savor the smell of?"

"That's ordinarily how it's done with plantings, to strengthen them," the gardener said.

"But what is the rationale?" the caliph asked.

"Manure protects the plant," the gardener said, "and helps it grow and send out shoots."

"Then we will protect it with another substance," the caliph said, and gave the order for musk to be pulverized in a sufficient qualntity to manure the whole garden, and this was carried out.

For one day and one night, the caliph sat there drinking, and when the sun came up he greeted it with another drink. Then he got up and ordered that the garden be sacked, and the gardeners and the eunuchs pillaged the musk from the narcissus bed, leaving the bulbs uprooted from from the soil, until the musk was gone and the garden was a barren waste. The cost of this quantity of musk was enormous.

One day, we were drinking with the caliph al-Radi bi-'llah in a courtyard that was shaded by a canopy of choice fruits, until he tired of sitting there and commanded that another seating area be prepared. "Scatter the carpets with fragrant herbs and lotus flowers, without the salvers and the usual arrangements for a smelling party. Do it quickly, now, so we can move our party over there."

In the blink of an eye, they told him it was done. "Stand up!" the caliph told us, and we followed him. But when he saw the room, it was not to his liking, and he instructed his sommeliers to sprinkle the herbs with powdered camphor to change their color. In they came with golden caskets full of powdered Rubahi camphor, and scattered it over the herbs by the scoopful. The caliph ordered them to add still more camphor, until the herbs were coated white, and looked like a green robe with downy cotton carded over it, or a garden struck by hoarfrost. "That's enough," the caliph said. I estimate the amount of camphor they used at over one thousand dry-weight measures, which is a lot.

So we sat and drank there with him. Then when the party was over he ordered the room to be sacked. and my servants gathered up many measures of camphor, along with the eunuchs and decorators and servants of the palace who did the same.

From Leavings of the Learned Gathering by al-Tanukhi

a.k.a. Table-Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge

tr. by David Larsen at 8:32 PM

Labels: Arabic prose

Concerning mice and cats, Abu 'l-Shamaqmaq said (meter: khafīf):

On the emptiness of my home, and empty

sacks and jars where meal should be, this is my poem.

Formerly, it was not desolate but guest-friendly,

prosperous, and in a flourishing state.

Now it seems that mice avoid my house

to refuge in a nobler steading.

The flies of my house and the crawling bugs

all beg to hit the road, away from where

the cat abides, and looks from side to side,

and no mouse does it spy the whole year through.

Its head swims up and down from extremity of hunger,

and a life of bitterness and vexation.

I said to the cat, when I saw its head hanging,

downcast with its gut aflame,

"Hang in there, kitty! best cat by far

my eyes have ever seen!"

"How can I hang on?" said the cat. "I cannot stay

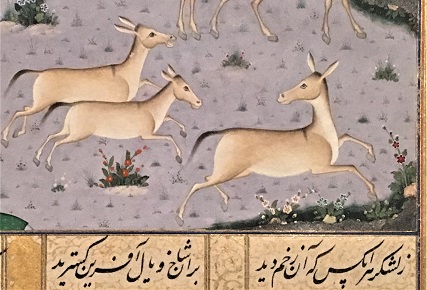

in a house that's empty as a wild ass's belly."

I said, "Go on to the neighbor’s house,

the one who brings home the fruits of commerce."

Meanwhile, spiders fill my pots and pans

and all my vessels with their spinning,

and off with the dogs, in the grip of dog-fever,

my dog runs mad astray.

From the Book of Animals of al-Jahiz

We are informed by Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-ʿArudi that Ahmad ibn Yahya attested these verses on the authority of al-Bahili (meter: kāmil):

Two confederates never seen together in one house,

each in movement for a set length of time.

Two separate colors in one sewn wrapper,

buffeted by winds and rains.

This describes Night and Day.

From The Ornament of the Learned Gathering

by Abu ʿAli Muhammad al-Hatimi

tr. by David Larsen at 7:45 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry , Lost works

Live by what you will. Weakness does not preclude success.

A man of expertise can still be duped.

A man who cannot learn from fate cannot be taught by people,

not even if they take him by the scruff.

What are hearts but inborn tempers?

How many hate their former friends?

Lend a hand in any land while you sojourn there.

Never say: "But I am alien to this place."

In favor of alliance with a stranger from afar,

nearby relations are sometimes severed.

And as long as a man may live, he is in denial.

Long life is his punishment.

From the Mu‘allaqa of ‘Abīd ibn al-Abraṣ

tr. by David Larsen at 11:49 PM

Labels: Arabic poetry

A Bedouin passed by a pontoon bridge, then gave a versified description of it unlike anything by anyone I know (meter: basīṭ):

Along the corniche, friends linger and disperse

by the Tigris post where the flood is spanned by a bridge of boats.

Viewed from one side, it's like a string of Bactrian camels

flanking each other crosswise in their tethers,

some followed by their young, some adolescents

treading dung, and some that are fair old milchers.

No coming home from travels for these camels.

Any time they move, their steps are short,

bound by ropes of palm dyed different colors

and fixed with pegs of iron in their sides.

One of the Unparalleled Poems from the Book of Prose and Poetry by

Ibn Abi Tahir Tayfur (d. 893 CE)

tr. by David Larsen at 11:09 AM

Labels: Arabic poetry

On the poet Abu 'l-‘Ibar al-Hashimi (d. 866 CE), by Sinan Antoon,

The Poetics of the Obscene in Premodern Arabic Poetry: Ibn al-Hajjaj

and Sukhf (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 40:

189 From the Book of Songs

189 From the Book of Songs

tr. by David Larsen at 2:32 PM

Labels: Arabic poetry , Secondary literature