We are informed by Tha‘lab that Ibn al-A‘rābī said: "Shams, Ashmus, and Shumūs are all said for the sun, as in the rajaz verse:

It was a day of solar oppression by Shumūs.

A similar instance [of the sun's name without the definite article] is in the verse by Abu 'l-Shīṣ (meter: ramal):

Just when the night's shadow is most pleasant,

Shams comes up and shade dissolves."

We are informed by Tha‘lab, on the authority of Salama ibn ‘Āṣim, that al-Farrā’ said: "The sun is called Dhukā’ ('Flammifera') and Bint Dhukā’ ('Daughter of Flammifera'). This name is indeclinable. It comes from dhakā yadhkū, a verb used of flames that burn high. And Ibn Dhukā’ ('Son of Flammifera') is a byname of the dawn." And he quoted the verse (meter: kāmil):

[The ostriches'] thoughts return to their their egg-deposit

when Dhukā’ stretches out her hand for the [night's] covers."

[....] We are informed by Tha‘lab that Ibn al-A‘rābī said: "The sun is called al-Jawna ('The Glowing Disk'), as in the rajaz verses:

Serve no milk, neither sour nor fresh,

that was not given in abundance,

[enough] to spread a pool for the clay to drink.

Even where al-Jawna hastens evaporation,

traces of the milk should last til nightfall.

Or the half-verse (meter: sarī‘):

...like a crafty [wolf] watching al-Jawna [go down].

"Jawn is white and black," he went on to say. "In the dialect of Quḍā‘a it is white, but for neighboring tribes it's black. Jawn can also be red."

[....] Tha‘lab said: "Al-Ulāha ('The Mighty Goddess') is the hot sun." And he reported that Ibn al-A‘rābī said: "Al-Ulāha, al-Ilāha and al-Alāha are names of the sun, and so is al-Hāla ('The Corona'), as in the verse (meter: ṭawīl):

Quick to startle [is my stallion! Head held high], like a child of Hāla,

[my horse] lives not by steady equanimity of mind.

"Al-Ḑiḥḥ ('The Glare') also is the sun," he went on to say. "Sahām are filaments of 'devil's mucus' [cobwebs encrusted with dust] that catch the sun. The iyāh of the sun is its brilliance, as are its iya’ and ayā’. And the iya’ of herbage is its lushness." And he recited the half-verse (meter: basīṭ):

The iya’ [of lush grass] met the iya’ of the sun, and together

the two were shining.

We are informed by Tha‘lab, on the authority of the son of Abū ‘Āmir al-Shaybānī, that Abū ‘Āmir said: "The 'tapering' [taṭarruf] of the sun comes just before it sinks below the horizon, as in the rajaz verse:

At the tapering of al-Shams's horn, he said his prayer."

Someone other than Tha‘lab points out that the sun is called al-Ghazāla ('The Gazelle') [perhaps explaining why the sun is said to have "horns"]. Others say that the sun's brightness and its spreading rays are called ‘ab’ or ‘ab. "The sun is pounding with its ṣalā’a," is said by another [to mean "The sun shines brightly"]: the ṣalā’a is a chemist's grindstone, used in the preparation of perfumes.

We are informed by Tha‘lab, on the authority of Salama ibn ‘Āṣim, that al-Farrā’ said: "A hot day is said to be shāmis and mashmūs ('sunny' and 'besunned'). The sun's uwār is its heat. The verbs zabba, zabbaba and azabba ('to hide beneath hair') are said of the sun's setting, as are ḍarra‘a and aḍra‘a ('to inch along') and karaba ('to succumb to fatigue')."

We are informed by Tha‘lab, on the authority of ‘Alī the son of Ṣāliḥ whose office it was to preserve the Prophet's prayer-mat, that al-Kisā’ī said: "Al-Ghazāla is said for the bright disk of the sun. 'Al-Ghazāla's horn is coming up,' one says [at sunrise]." And we are informed by Tha‘lab, on the authority of Ibn Najda, that Abū Zayd al-Anṣārī said: "The 'gazelles of forenoon' is an expression for the day's rising," and that he recited the rajaz verses:

"Who loves night travel in the frigid season?"

asks the tribe. "Is there a young hero we can call on,

one whose strength is neither faint nor ragged,

to set the tribe moving with the gazelles of forenoon?"

We are informed by Tha‘lab on the authority of Ibn al-A‘rābī that the circle that sometimes forms around the sun is called al-ihrāt. As for al-falak, it is an 'orbit' around the heavens' axis. God, be He exalted, says [in Sūrat al-Anbiyā’ 21:33]: 'All are in a falak swimming.'" According to another authority cited by Tha‘lab, where sunlight strikes trees and the ground it is called maḍḥāh and ḍāḥiya, and where it does not strike them it is called maqnāh and maqnuwa. And he recited the verse (meter: ṭawīl):

We came upon him in the sunless maqnuwa, where

a teak-grove cast its decorous veil over al-Shams.

Another authority attests the verse (meter: ṭawīl):

Herbage grows thin on one side of the mountain. On the other side,

it is lush. The overcast light of day lands on both sides.

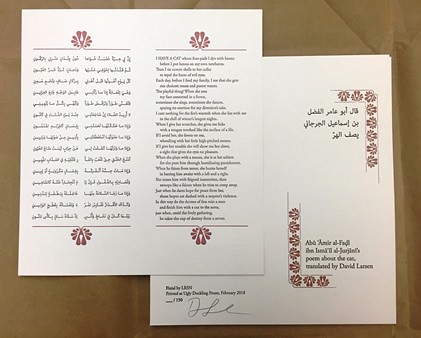

From The Book of Day and Night in [the Arabic] Language by Abū ‘Umar

Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wāḥid al-Muṭarriz al-Zāhid, better known as Ghulām Tha‘lab